Difference between revisions of "Cnidoscolus stimulosus"

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

===Fire ecology===<!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology===<!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | Populations of ''Cnidoscolus stimulosus'' have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> | + | Populations of ''Cnidoscolus stimulosus'' have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref><ref>Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> |

This species is included in the flowering plant survery – post burn – in Heuberger’s study.<ref>Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.</ref> ''Cnidoscolus stimulosus'' was one of the plant species to increase in abundance recovery post-fire in Rosemary scrub ecosystem.<ref>Menges, E. S. and N. M. Kohfeldt (1995). "Life History Strategies of Florida Scrub Plants in Relation to Fire." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122(4): 282-297.</ref> ''Cnidoscolus stimulosus'' also resprouted post-burn after fire was reinstated into the ecosystem.<ref>Reinhart, K. O. and E. S. Menges (2004). "Effects of re-introducing fire to a central Florida sandhill community." Applied Vegetation Science 7: 141-150.</ref> | This species is included in the flowering plant survery – post burn – in Heuberger’s study.<ref>Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.</ref> ''Cnidoscolus stimulosus'' was one of the plant species to increase in abundance recovery post-fire in Rosemary scrub ecosystem.<ref>Menges, E. S. and N. M. Kohfeldt (1995). "Life History Strategies of Florida Scrub Plants in Relation to Fire." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122(4): 282-297.</ref> ''Cnidoscolus stimulosus'' also resprouted post-burn after fire was reinstated into the ecosystem.<ref>Reinhart, K. O. and E. S. Menges (2004). "Effects of re-introducing fire to a central Florida sandhill community." Applied Vegetation Science 7: 141-150.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:48, 22 July 2021

| Cnidoscolus stimulosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Euphorbiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Genus: | Cnidoscolus |

| Species: | C. stimulosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cnidoscolus stimulosus (Michx.) Govaerts | |

| |

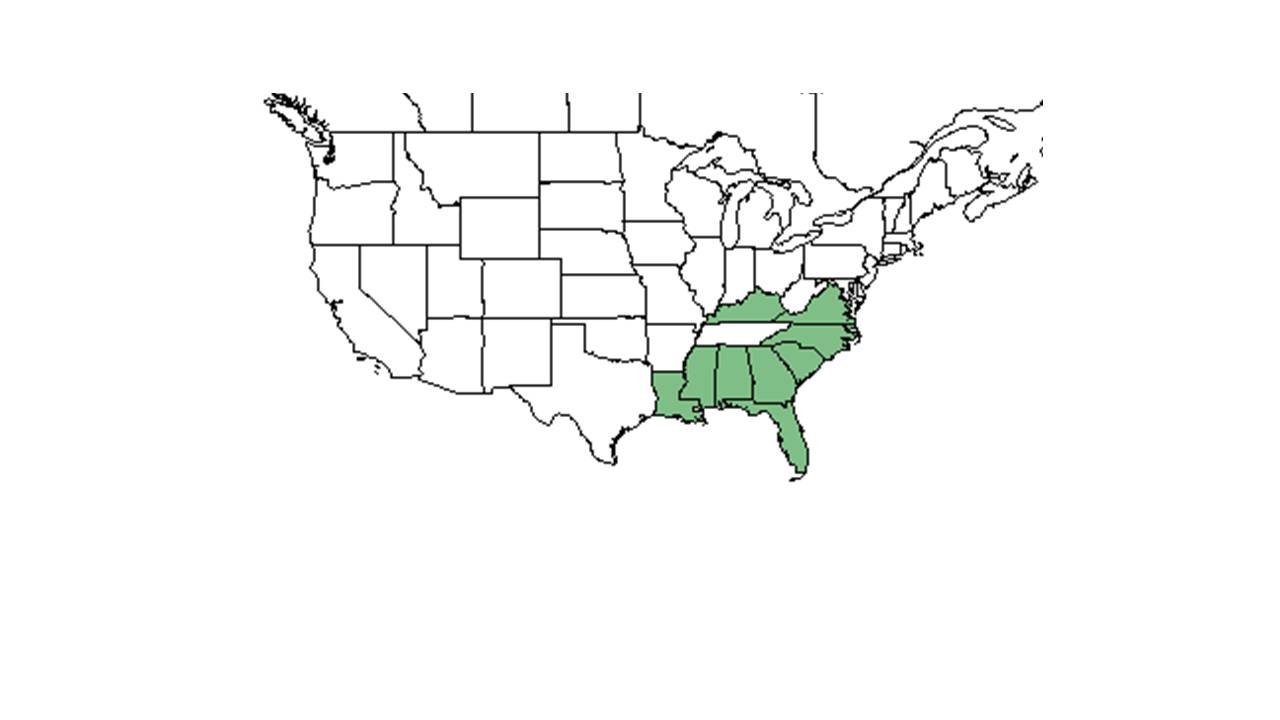

| Natural range of Cnidoscolus stimulosus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Finger-rot; Spurge-nettle; Tread-softly; Bull-nettle

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Cnidoscolus urens (Linnaeus) Arthur var. stimulosus (Michaux) Govaerts; Bivonea stimulosa (Michaux) Rafinesque.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

Cnidoscolus stimulosus is a herbaceous, monoecious, erect or reclining perennial, growing 5 - 100 cm tall with palmately dissected or lobed, alternate leaves. The entire plant is covered with stinging hairs and grows from an erect tuberous base.[2] The leaf lobes or dissections are prominently dentate, very rarely entire. The inflorescence is terminal and compound, with two flower clusters branching from under a central terminal flower, and often appears axillary because of the elongation of axillary branches with terminal inflorescence. The central flower in each is usually pistillate (female) while the lateral are usually staminate (male). The calyx is white in color, forming a narrow 1 - 1.5 cm long tube with petals abruptly bent at right angles. The petals are absent. There are 10 - 30 stamens, united at the base. There are 3 stigmas, each with 3 - 5 lobes. The capsule is 3-locular, each locule is 1-seeded. The seeds are dark-brown in color, growing 8 - 9 mm long and 4 - 5 mm broad, with a conspicuous projection growth at the base.[3]

The root system of Cnidoscolus stimulosus includes root tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[4]. Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 162.4 mg/g (ranking 30 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 57.1 % (ranking 4 out of 100 species studied).[4]

Distribution

C. stimulosus is native to the southeast Coastal Plain in the United States, ranging from Kentucky and Virginia south to Louisiana and Florida, excluding Arkansas and Tennessee.[5] Although this species is sometimes treated as a variety of C. urens, C. stimulosus has a different distribution than C. urens, which ranges from Mexico and Central America south to northern South America.[6]

Ecology

Habitat

Cnidoscolus stimulosus is found in sparsely canopied upland habitats that occur on deep, well drained, sandy substrate suitable for construction of Gopher tortoise burrows. It also occurs in dry sandy flatwoods,[7] sandy barrens, mixed hardwood hammocks, sand dunes, longleaf pine-wiregrass-scrub oak sand ridges,[2] and mesic longleaf pine savannas.[8] Cnidoscolus stimulosus is a feature of sandhill communities with frequent occurrence in the understory.[9] Finally, it occurs in some disturbed areas, such as roadsides, old fields, bulldozed clearings, railways, and residential lawns.[2] C. stimulosus responds negatively to agriculture related soil disturbance in South Carolinian coastal plains.[10] C. stimulosus also responds positively to disking in Southern Georgia, especially in double-disked plots where its density was highest.[11]

Cnidoscolus stimulosusis an indicator species for the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Phenology

It has three seeds fruit and produce seeds with elaiosomes.[9]

C. stimulosus has been observed flowering January through August, October and December with peak inflorescence in April.[13][2] Fruiting was observed April through August and in December.

This species has been observed to flower within three months following burning.[14] It has also been shown to have peak production (including flowering) on double-disked plots on the second year of study.[15]

Seed dispersal

“In all of these species, seeds are forcefully expelled after the fruit matures and dries. Three of the ballistic euphorbs (C. stimulosus, C. argyranthemus and S. sylvatica) produce seeds with elaiosomes and all of the ballistic species are collected by ants, in particular Pogonomyrex badius Latreille (Long and Lakela 1971; N.E. Stamp and J. R. Lucas, personal observation).” [9] This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence. [16] The ant preference for C. stimulosus might be due to the elaiosome and its chemical composition.[17]

Fire ecology

Populations of Cnidoscolus stimulosus have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[18][19]

This species is included in the flowering plant survery – post burn – in Heuberger’s study.[20] Cnidoscolus stimulosus was one of the plant species to increase in abundance recovery post-fire in Rosemary scrub ecosystem.[21] Cnidoscolus stimulosus also resprouted post-burn after fire was reinstated into the ecosystem.[22]

It resprouts and flowers within two months of burning in the growing season.KMR In southeastern Polk County, C. stimulosus was observed blooming 54 days after a prescribed burn on December 22, 2016.[8] Similarly, in Charlotte County, FL, it was observed blooming about 19 days post burn.[23] C. stimulosus was shown to slightly increase in occurrence in winter and spring burns, rather than summer burn regiments; it seemed to benefit the most as a whole to spring burns.[24] Overall, the species appears to be tolerant of fire, and potentially benefits from it, but it does not seem to be dependent on the presence of fire on the landscape.[2]

Pollination and use by animals

Seeds were found in middens of harvester-ant nests of Pogonomyremex badius Latreille. In addition, seeds of all three plant species were observed being carried into the ant nests and then later deposited uneaten at the nest perimeter.[9] Gopher tortoises (juveniles and adults) feed on Cnidoscolus stimulosus. Included in gopher tortoises’ scat.[25][26] It consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for terrestrial birds.[27] C. stimulosus also consists of less than 1% of the diet for northern bobwhite quail in the southeast.[28] However, it is considered to have poor forage value.[29]

Diseases and parasites

C. stimulosus is a host plant for the false spider mite (Brevipalpus obovatus) in North America.[30]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: H. E. Ahles, L. C. Anderson, W. R. Anderson, L. Baltzell, D. Burch, K. C. Burks, R. J. Campana, J. Carmichael, A. F. Clewell, D. Demaree, F. S. Earle, P. Elliot, D. L. Fichtner, T. Floyd, E. Freeman, W. B. Fox, H. Gale, M. A. Garland, H. E. Grelen, W. T. Gillis, R. K. Godfrey, J. Haesloop, B. K. Holst, C. Hudson, P. Jones, W. Kittredge, G. R. Knight, R. Komarek, R. Kral, D. W. Mather, S. McDaniel, R. S. Mitchell, S. J. Noyes, K. Oakes, G. W. Ramsey, G. W. Reinert, A. B. Seymour, D. B. Ward, J. H. Wiese, and R. L. Wilbur. States and Counties: Alabama: Geneva. Florida: Alachua, Bay, Broward, Calhoun, Citrus, Dade, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Monroe, Nassau, Okaloosa, Orange, Pasco, Pinellas, Sarasota, Suwannee, and Wakulla. Georgia: Bullock, Grady, and Thomas. Mississippi: near Ocean Springs, George, and Forrest. North Carolina: Carteret, Cleveland, Cumberland, Duplin, Harnett, Hertford, and Pender.

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 661-2. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 8 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, et al. (2003). [Abstract] Long-term seasonal burning at the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, north Florida: changes in the sandhill plots after 23 years. Second International Wildland Fire Ecology and Fire Management Congress and Fifth Symposium on Fire and Forest Meteorology, Orlando, FL, American Meteorological Society.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Observation by Edwin Bridges in southeastern Polk County, FL, February 14, 2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group February 15, 2017.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Stamp, N. E. and J. R. Lucas (1990). "Spatial patterns and dispersal distances of explosively dispersing plants in Florida sandhill vegetation." Journal of Ecology 78: 589-600.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Buckner, J.L. and J.L. Landers. (1979). Fire and Disking Effects on Herbaceous Food Plants and Seed Supplies. The Journal of Wildlife Management 43(3):807-811.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kevin Robertson personal observation at Pebble Hill Plantation, Georgia and Tall Timbers Research Station, Florida, July 2015.

- ↑ Buckner, J. L. and J. L. Landers (1979). "Fire and disking effects on herbaceous food plants and seed supplies." Journal of Wildlife Management 43: 807-811.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Cumberland, M. S. and L. K. Kirkman (2013). "The effects of the red imported fire ant on seed fate in the longleaf pine ecosystem." Plant Ecology 214: 717-724.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ Menges, E. S. and N. M. Kohfeldt (1995). "Life History Strategies of Florida Scrub Plants in Relation to Fire." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122(4): 282-297.

- ↑ Reinhart, K. O. and E. S. Menges (2004). "Effects of re-introducing fire to a central Florida sandhill community." Applied Vegetation Science 7: 141-150.

- ↑ Observation by Jake Antonio Heaton in Charlotte County, FL, May 22, 2016, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group May 23, 2016.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Birkhead, R. D., C. Guyer, et al. (2005). "Patterns of folivory and seed ingestion by gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus) in a southeastern pine savanna." American Midland Naturalist 154: 143-151

- ↑ Mushinsky, H. R., Terri A. Stilson and Earl D. McCoy (2003). "Diet and Dietary Preference of the Juvenile Gopher Tortoise " Herpetologists' League 59(4): 475-486.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Laessle, A. M. and O. E. Frye (1956). "A Food Study of the Florida Bobwhite Colinus virginianus floridanus (Coues)." The Journal of Wildlife Management 20(2): 125-131.

- ↑ Hilman, J. B. (1964). "Plants of the Caloosa Experimental Range " U.S. Forest Service Research Paper SE-12

- ↑ Childers, C. C., et al. (2003). "Host plants of Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, and B. phoenicis (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) and their potential involvement in the spread of viral diseases vectored by these mites." Experimental & Applied Acarology 30: 29-105.