Difference between revisions of "Vitis rotundifolia"

(→Habitat) |

(→Habitat) |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

<!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | ''V. rotundifolia'' has been found in sand pine-oak scrub sand ridges, titi swamps, floodplain woodlands, live oak hammocks, slash pine flatwoods, fresh water marshes, wet pine flatwoods, swampy woodlands, river banks, canal banks, and pine-oak woodlands.<ref name="FSU"> Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Sydney T. Bacchus, Tom Barnes, Delzie Demaree, D. L. Fichtner, Robert K. Godfrey, Beverly Judd, Walter S. Judd, and Deborah R. Shelley. States and counties: Florida: Franklin, Indian River, Highlands, Leon, Liberty, Seminole, and Wakulla.</ref> It is also found in disturbed areas like roadsides.<ref name="FSU"/> | + | ''V. rotundifolia'' has been found in sand pine-oak scrub sand ridges, titi swamps, floodplain woodlands, live oak hammocks, slash pine flatwoods, fresh water marshes, wet pine flatwoods, swampy woodlands, river banks, canal banks, and pine-oak woodlands.<ref name="FSU"> Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Sydney T. Bacchus, Tom Barnes, Delzie Demaree, D. L. Fichtner, Robert K. Godfrey, Beverly Judd, Walter S. Judd, and Deborah R. Shelley. States and counties: Florida: Franklin, Indian River, Highlands, Leon, Liberty, Seminole, and Wakulla.</ref> It is also found in disturbed areas like roadsides.<ref name="FSU"/> |

| + | ''V. rotundifolia'' responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.</ref> However, it responds positively to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina<ref>Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.</ref> and exhibits positive as well as negative responses to heavy silvilculture in North Florida.<ref>Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to ''Pinus elliottii'' Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.</ref> ''V. rotundifolia'' responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in North Florida.<ref>Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.</ref> It exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.<ref>McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.</ref> ''V. rotundifolia'' responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.<ref>Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.</ref> | ||

| − | '' | + | Associated species: ''Pinus elliottii var. densa, P. clausa, Quercus myrtifolia, Bumelia tenax, Xymenia americana, Persea palustris, Lyonia ferruginea, Palafoxia feayi, Sabal etonia, Quercus geminata, Q. inopina, Carya floridana, Persea humilis, Opuntia humifusa, Smilax auriculata, Vitis munsoniana Prunus geniculata'', and ''Polygonella fimbriata''.<ref name="FSU"/> |

''Vitis rotundifolia'' is frequent and abundant in the Calcareous Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ''Vitis rotundifolia'' is frequent and abundant in the Calcareous Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 15:25, 21 June 2021

| Vitis rotundifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Rhamnales |

| Family: | Vitaceae |

| Genus: | Vitis |

| Species: | V. rotundifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Vitis rotundifolia Michx. | |

| |

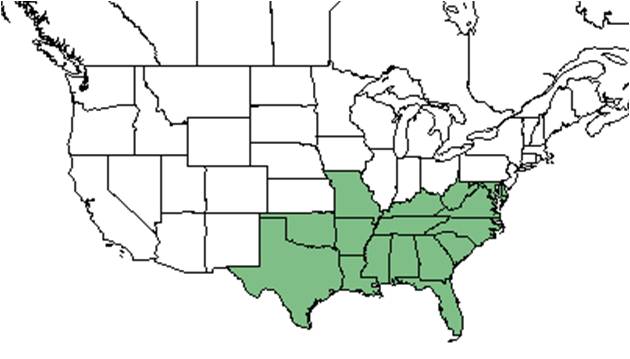

| Natural range of Vitis rotundifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Muscadine

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Muscadinia munsoniana (Simpson ex Munson) Small; Muscadinia rotundifolia (Michaux) Small.[1]

Variations: Vitis rotundifolia var. munsoniana Simpson ex Munson.[2]

Description

"High-climbing or trailing vines; pith brown, continuous or discontinuous through the nodes. Leaves simple, acute or acuminate, serrate, base cordate, petiolate. Inflorescences paniculate. Calyx flat, round, usually without lobes; petals 5, 0.5-2.5 mm long, cohering at the summit, separating at the base, falling at anthesis; disk of 5 connate or separate glands, 0.2-0.4 mm long; stigmas small, style conical, 0.2-0.5 mm long. Berry dark purple, globose; seeds 1-4 usually red or brown, pyriform, 4-7 mm long."[3]

"High-climbing vine with adhering bark, conspicuous tendrils, and pith continuous through node; young branches angled, puberulent. Leaves suborbicular or widely ovate, to 8 cm long or wide, glabrate or glabrous. Mature inflorescences to 5 cm long, few-fruited; berries 1-2 cm in diam.; seeds ca. 6 mm long."[3]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

V. rotundifolia has been found in sand pine-oak scrub sand ridges, titi swamps, floodplain woodlands, live oak hammocks, slash pine flatwoods, fresh water marshes, wet pine flatwoods, swampy woodlands, river banks, canal banks, and pine-oak woodlands.[4] It is also found in disturbed areas like roadsides.[4] V. rotundifolia responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.[5][6] However, it responds positively to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina[7] and exhibits positive as well as negative responses to heavy silvilculture in North Florida.[8] V. rotundifolia responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in North Florida.[9] It exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[10] V. rotundifolia responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[11]

Associated species: Pinus elliottii var. densa, P. clausa, Quercus myrtifolia, Bumelia tenax, Xymenia americana, Persea palustris, Lyonia ferruginea, Palafoxia feayi, Sabal etonia, Quercus geminata, Q. inopina, Carya floridana, Persea humilis, Opuntia humifusa, Smilax auriculata, Vitis munsoniana Prunus geniculata, and Polygonella fimbriata.[4]

Vitis rotundifolia is frequent and abundant in the Calcareous Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Phenology

V. rotundifolia has been observed flowering from March to May and in July with peak inflorescence in May.[13]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[14]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Vitis rotundifolia at Archbold Biological Station:[15]

Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens

Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochloropsis anonyma, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum placidensis

Megachilidae: Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, M. mendica, M. petulans

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Vitis rotundifolia produces an edible drupe that can be eaten raw or made into goods such as jelly or wine.[16]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 695. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Sydney T. Bacchus, Tom Barnes, Delzie Demaree, D. L. Fichtner, Robert K. Godfrey, Beverly Judd, Walter S. Judd, and Deborah R. Shelley. States and counties: Florida: Franklin, Indian River, Highlands, Leon, Liberty, Seminole, and Wakulla.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 15 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Hardin, J.W., Arena, J.M. 1969. Human Poisoning from Native and Cultivated Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.