Difference between revisions of "Rhus copallinum"

(→Cultural use) |

(→Ecology) |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

Fire stimulates root and root collar sprouting along with enhancing germination, making this a fire-climax species. Density declines 3 to 4 years following a fire, with fire exclusion reducing density and cover.<ref name="fs"/> Seeds respond positively to heat shock, suggesting that its germination is dependent on or facilitated by fire.<ref>Bolin, J. F. 2009. Heat shock germination responses of three eastern North American temperate species. Castanea, v. 74, no. 2, p. 160-167.</ref> | Fire stimulates root and root collar sprouting along with enhancing germination, making this a fire-climax species. Density declines 3 to 4 years following a fire, with fire exclusion reducing density and cover.<ref name="fs"/> Seeds respond positively to heat shock, suggesting that its germination is dependent on or facilitated by fire.<ref>Bolin, J. F. 2009. Heat shock germination responses of three eastern North American temperate species. Castanea, v. 74, no. 2, p. 160-167.</ref> | ||

| − | ===Pollination=== | + | ===Pollination and use by animals=== |

| + | |||

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of ''Rhus copallinum'' at Archbold Biological Station:<ref>Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowering plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.</ref> | The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of ''Rhus copallinum'' at Archbold Biological Station:<ref>Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowering plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.</ref> | ||

| Line 67: | Line 68: | ||

Vespidae: ''Eumenes fraternus'', ''Monobia quadridens'', ''Pachodynerus erynnis'', ''Parancistrocerus fulvipes rufovestris'', ''Parancistrocerus perennis anacardivora'', ''Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus'', ''Polistes dorsalis hunteri'', ''Stenodynerus beameri'', ''Stenodynerus pulvinatus surrufus'', ''Vespula maculifrons'', ''Vespula squamosa'', ''Zethus spinipes'' | Vespidae: ''Eumenes fraternus'', ''Monobia quadridens'', ''Pachodynerus erynnis'', ''Parancistrocerus fulvipes rufovestris'', ''Parancistrocerus perennis anacardivora'', ''Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus'', ''Polistes dorsalis hunteri'', ''Stenodynerus beameri'', ''Stenodynerus pulvinatus surrufus'', ''Vespula maculifrons'', ''Vespula squamosa'', ''Zethus spinipes'' | ||

| − | + | ||

The foliage is a food source for the caterpillar ''Pyrrhia umbra''.<ref name="illinois">[[http://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/trees/plants/winged_sumac.htm]]Accessed: March 10, 2016</ref> The berries are eaten by wild turkeys and songbirds.<ref name="fs"/> Birds have been observed to choose fruits of ''R. copallina'' rather than fruits of ''R. glabra'' when they were both available as winter foods. This could be due to the higher caloric value and larger fruits of ''R. copallinum''.<ref name="graber">Graber, J. W. and P. M. Powers (1981). "Dwarf Sumac as Winter Bird Food." The American Midland Naturalist 105(2): 410-412.</ref> | The foliage is a food source for the caterpillar ''Pyrrhia umbra''.<ref name="illinois">[[http://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/trees/plants/winged_sumac.htm]]Accessed: March 10, 2016</ref> The berries are eaten by wild turkeys and songbirds.<ref name="fs"/> Birds have been observed to choose fruits of ''R. copallina'' rather than fruits of ''R. glabra'' when they were both available as winter foods. This could be due to the higher caloric value and larger fruits of ''R. copallinum''.<ref name="graber">Graber, J. W. and P. M. Powers (1981). "Dwarf Sumac as Winter Bird Food." The American Midland Naturalist 105(2): 410-412.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 12:44, 17 June 2021

| Rhus copallinum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Michelle Smith | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Tracheophyta- Vascular plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Anacardiaceae |

| Genus: | Rhus |

| Species: | R. copallinum |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhus copallinum L. | |

| |

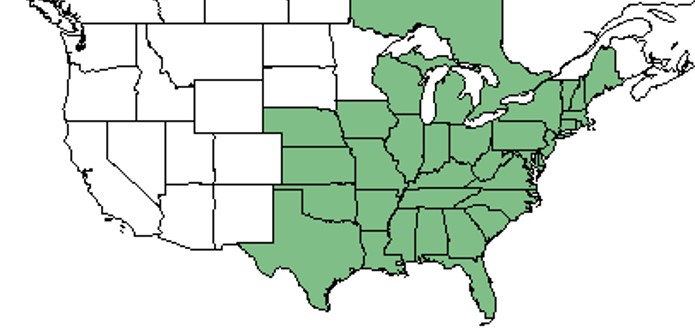

| Natural range of Rhus copallinum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Winged sumac, Flameleaf sumac, Shining sumac

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Rhus copallina L.; Rhus leucantha Jacquin; Rhus obtusifolia (Small) Small.[1]

Varieties: R. copallinum Linnaeus var. latifolia Engler.[2]

Description

"Upright shrubs or small trees, not poisonous. Leaves once-pinnately compound. Inflorescence a terminal panicle. Drupes red, ripening in the autumn. Seeds smooth. Flowers produced after the leaves."[3] "Rhizomatous shrub or small tree to 7 m tall; stems densely short-pubescent. Leaflets 9-23 (mostly 9-11), sessile, oblong to elliptic, 3-8 cm long, 1-4 cm wide, acute to acuminate, entire or less frequently crenate to serrate, base cuneate to rarely rounded, glabrous or densely pubescent beneath; rachis winged. Panicle 0.5-3 dm long and usually as broad. Drupe densely short-pubescent, 3-4 mm broad. Seeds 2.5-3 mm long."[3]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

R. copallinum habitats include old fields, oak-hickory woods, oak scrubs, marsh banks, roadsides, and sand ridges.[4] R. copallinum responds positively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for post-agricultural woodland.[5][6] It responds positively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[7] R. copallinum responds both positively and negatively to soil disturbance by a KG blade and positively to disturbance by roller chopping in East Texas Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forests.[8]

Rhus copallinum is frequent and abundant in the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[9]

Phenology

This species has been observed to flower from July to August.[10][11]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[12]

Seed bank and germination

The rhizomes, flowers, fruits, senescent leaves and leaf litter contain toxins that significantly inhibit both seed germination and seedling growth of climax prairie and weedy species.[13] Seed germination responds positively to heat shock with highest germination rates at 90 C.[14]

Fire ecology

Fire stimulates root and root collar sprouting along with enhancing germination, making this a fire-climax species. Density declines 3 to 4 years following a fire, with fire exclusion reducing density and cover.[15] Seeds respond positively to heat shock, suggesting that its germination is dependent on or facilitated by fire.[16]

Pollination and use by animals

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Rhus copallinum at Archbold Biological Station:[17]

Colletidae: Colletes mandibularis

Halictidae: Augochlora pura, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis sumptuosa, Lasioglossum pectoralis, L. placidensis

Leucospididae: Leucospis robertsoni

Megachilidae: Coelioxys sayi, Megachile xylocopoides

Pompilidae: Episyron conterminus posterus, Poecilopompilus interruptus, Tachypompilus f. ferrugineus

Sphecidae: Cerceris flavofasciata floridensis, C. tolteca, Ectemnius rufipes ais, Isodontia apicalis, Oxybelus decorosum, Palmodes dimidiatus, Philanthus ventilabris, Sphex ichneumoneus, Tachysphex similis

Vespidae: Eumenes fraternus, Monobia quadridens, Pachodynerus erynnis, Parancistrocerus fulvipes rufovestris, Parancistrocerus perennis anacardivora, Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus, Polistes dorsalis hunteri, Stenodynerus beameri, Stenodynerus pulvinatus surrufus, Vespula maculifrons, Vespula squamosa, Zethus spinipes

The foliage is a food source for the caterpillar Pyrrhia umbra.[18] The berries are eaten by wild turkeys and songbirds.[15] Birds have been observed to choose fruits of R. copallina rather than fruits of R. glabra when they were both available as winter foods. This could be due to the higher caloric value and larger fruits of R. copallinum.[19]

Diseases and parasites

Fusarium wilt infects the roots, causing the leaves to droop and wilt.[20]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

The fruits are used to make a sweet drink by the Cherokee Indians.[21] The drink was similar to what we think of as pink lemonade. Additionally, boiling the berries can create a cure for sore throats.[22]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 678. Print.

- ↑ Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2016. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Tom Barnes, Kathy Craddock Burks, G. Fleming, P. Genelle, Robert K. Godfrey, Gary R. Knight. States and Counties: Florida: Florida: Citrus, Franklin, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, St. Johns, Wakulla.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Stransky, J.J., J.C. Huntley, and Wanda J. Risner. (1986). Net Community Production Dynamics in the Herb-Shrub Stratum of a Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest: Effects of CLearcutting and Site Preparation. Gen. Tech. Rep. SO-61. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Dept of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station. 11 p.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ [[1]]Missouri Botanical Gardens. Accessed: March 7, 2016

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 19 MAY 2021

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, Jones Ecological Research Center, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ Petranka, J. W. and J. K. McPherson (1979). "The Role of Rhus Copallina in the Dynamics of the Forest-Prairie Ecotone in North-Central Oklahoma." Ecology 60(5): 956-965.

- ↑ Bolin, J. F. 2009. Heat shock germination responses of three eastern North American temperate species. Castanea, v. 74, no. 2, p. 160-167.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedfs - ↑ Bolin, J. F. 2009. Heat shock germination responses of three eastern North American temperate species. Castanea, v. 74, no. 2, p. 160-167.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowering plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ [[2]]Accessed: March 10, 2016

- ↑ Graber, J. W. and P. M. Powers (1981). "Dwarf Sumac as Winter Bird Food." The American Midland Naturalist 105(2): 410-412.

- ↑ [[3]]University of Florida Extension Accessed: March 10, 2016

- ↑ Deuerling D., Lantz P. 1991 Native Wild Foods: Indian Lemonade. Palmetto 11(3):7

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.