Difference between revisions of "Quercus laevis"

(→Taxonomic notes) |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Q. laevis'' has been found in sandy scrub, scrub oak sand ridge, open pine-oak woodland, and open longleaf pine forest.<ref name="FSU"> Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, George R. Cooley, R. A. Davidson, Robert K. Godfrey, Robert L. Lazor, Joseph Monachino, and R. F. Thorne. States and counties: Florida: Franklin, Hernando, Leon, and Okaloosa.</ref> It is also found in disturbed areas like secondary slash pine forest.<ref name="FSU"/> Associated species:''Q. incana, Baptisia lecontei, Pteridium aquilinum, Sassafras albidum, Bapitisa lecontei, Pteridium aquilinum'', and ''Sassafras albidum''.<ref name="FSU"/> | ||

| + | |||

''Quercus laevis'' is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.<ref name=ost>Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.</ref> | ''Quercus laevis'' is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.<ref name=ost>Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.</ref> | ||

''Q. laevis'' responds negatively to agriculture-based soil disturbance in historically longleaf forest communities.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref> It also responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.</ref> It also responds positively to roller chopping in West Florida with an overall increase in density.<ref>Burns, R.M. and R.D. McReynolds. (1972). Scheduling and Intensity of Site Preparation for Pine in West Florida Sandhills. Journal of Forestry 70(12):737-740.</ref> When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, ''Q. laevis'' responds negatively by way of absence.<ref>Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.</ref> ''Q. laevis'' responds negatively to soil disturbance by roller chopping in Northwest Florida sandhills.<ref>Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.</ref> ''Quercus laevis'' is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills and Panhandle Xeric Sandhills community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ''Q. laevis'' responds negatively to agriculture-based soil disturbance in historically longleaf forest communities.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref> It also responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.</ref> It also responds positively to roller chopping in West Florida with an overall increase in density.<ref>Burns, R.M. and R.D. McReynolds. (1972). Scheduling and Intensity of Site Preparation for Pine in West Florida Sandhills. Journal of Forestry 70(12):737-740.</ref> When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, ''Q. laevis'' responds negatively by way of absence.<ref>Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.</ref> ''Q. laevis'' responds negatively to soil disturbance by roller chopping in Northwest Florida sandhills.<ref>Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.</ref> ''Quercus laevis'' is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills and Panhandle Xeric Sandhills community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:17, 8 June 2021

| Quercus laevis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Tracheophyta- Vascular plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Quercus |

| Species: | Q. laevis |

| Binomial name | |

| Quercus laevis Walter | |

| |

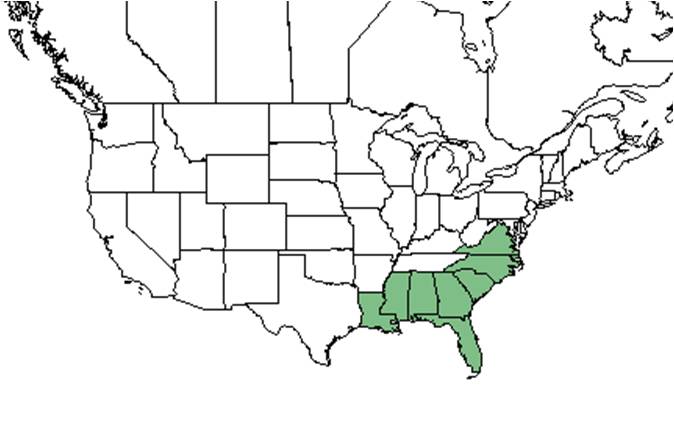

| Natural range of Quercus laevis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Turkey oak

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Quercus catesbaei Michaux.[1]

Description

A description of Quercus laevis is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

Q. laevis has been found in sandy scrub, scrub oak sand ridge, open pine-oak woodland, and open longleaf pine forest.[2] It is also found in disturbed areas like secondary slash pine forest.[2] Associated species:Q. incana, Baptisia lecontei, Pteridium aquilinum, Sassafras albidum, Bapitisa lecontei, Pteridium aquilinum, and Sassafras albidum.[2]

Quercus laevis is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.[3] Q. laevis responds negatively to agriculture-based soil disturbance in historically longleaf forest communities.[4] It also responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.[5][6] It also responds positively to roller chopping in West Florida with an overall increase in density.[7] When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, Q. laevis responds negatively by way of absence.[8] Q. laevis responds negatively to soil disturbance by roller chopping in Northwest Florida sandhills.[9] Quercus laevis is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills and Panhandle Xeric Sandhills community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[10]

Phenology

Quercus laevis has been observed to flower from March to June.[11]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[12]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, George R. Cooley, R. A. Davidson, Robert K. Godfrey, Robert L. Lazor, Joseph Monachino, and R. F. Thorne. States and counties: Florida: Franklin, Hernando, Leon, and Okaloosa.

- ↑ Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Burns, R.M. and R.D. McReynolds. (1972). Scheduling and Intensity of Site Preparation for Pine in West Florida Sandhills. Journal of Forestry 70(12):737-740.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 19 MAY 2021

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.