Difference between revisions of "Liatris laevigata"

Emmazeitler (talk | contribs) |

Emmazeitler (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

<!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | <!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | It has been observed to have a strong fire-dependent blooming behavior, blooming in large numbers in pinelands that have been burned recently, and rarely blooming or not at all in pinelands that have been unburned for more than two years.<ref name="Herndon 1987"/> Anderson and Menges<ref name="A&M 1997"/> found that ''L. tenuifolia var. laevigata'' responded quickly and strongly to burning and blooms at high rates in the year following a fire. This study also found that concentrations of Nitrogen, Phosphorous, Potassium, and Iron were 2 to 6 fold higher in individuals in burned areas compared to those in unburned areas. The root length of individuals is also longer in burned sites. | + | It has been observed to have a strong fire-dependent blooming behavior, blooming in large numbers in pinelands that have been burned recently, and rarely blooming or not at all in pinelands that have been unburned for more than two years.<ref name="Herndon 1987">Herndon A. 1987. Variation in Resource Allocation and Reproductive Effort within a Single Population of Liatris laevigata Nuttall (Asteraceae). ''The American Midland Naturalist''. 118(2): 406-413.</ref> Anderson and Menges<ref name="A&M 1997">Anderson RC, Menges ES. 1997. Effects of Fire on Sandhill Herbs: Nutrients, Mycorrhizae, and Biomass Allocation. ''American Journal of Botany''. 84(7): 938.</ref> found that ''L. tenuifolia var. laevigata'' responded quickly and strongly to burning and blooms at high rates in the year following a fire. This study also found that concentrations of Nitrogen, Phosphorous, Potassium, and Iron were 2 to 6 fold higher in individuals in burned areas compared to those in unburned areas. The root length of individuals is also longer in burned sites. |

| + | |||

===Pollination=== | ===Pollination=== | ||

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of ''Liatris laevigata'' at Archbold Biological Station:<ref>Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowering plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.</ref> | The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of ''Liatris laevigata'' at Archbold Biological Station:<ref>Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowering plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:55, 23 September 2020

| Liatris laevigata | |

|---|---|

Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Liatris |

| Species: | L. laevigata |

| Binomial name | |

| Liatris laevigata (Nutt.) Small | |

| |

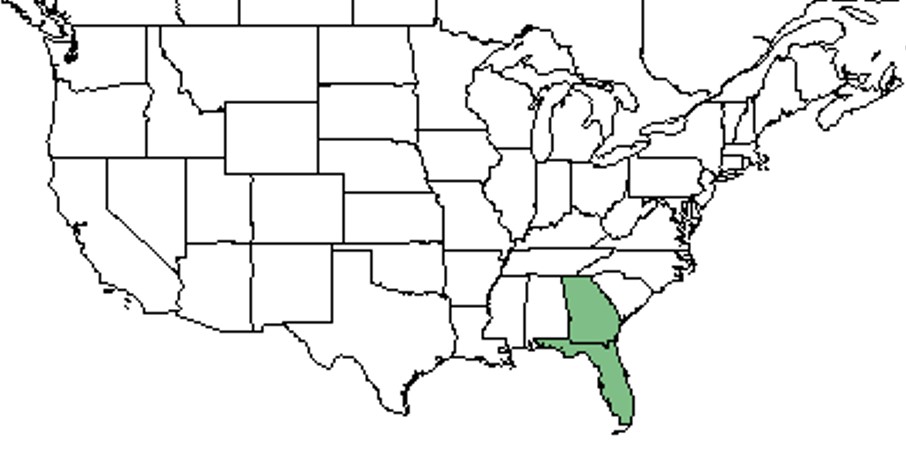

| Natural range of Liatris laevigata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Shortleaf blazing star; Smooth blazing star[1]; shortleaf gayfeather; Clusterleaf gayfeather

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Liatris tenuifolia Nuttall var. quadriflora Chapman; Laciniaria tenuifolia (Nuttall) Kuntze.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Sometimes L. laevigata is classified as a variety of L. tenuifolia, however, they have distinct characteristics. L. laevigata can be distinguishable from L. tenuifolia by having wider and coarser leaves.[2]

Description

A description of Liatris laevigata is provided in The Flora of North America.

L. laevigata is a perennial species that consist of a globose corm, glabrous stem, basal and proximal cauline leaves.[3] The inflorescence consists of a scape with reduced leaves and many purple flower heads.[4]

Distribution

Restricted to peninsular Florida and adjacent Georgia.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats are well-drained sandy soils such as longleaf pine-saw palmetto flats; ecotones between longleaf pine turkey oak sand ridges and pine flatwoods; scrub oak-wiregrass ridges; Pinus clausa/Ceratiola scrubs; Quercus laurifolia hammocks; and pine flatwoods on limerock. It has occurred in disturbed areas such as roadsides, sandy fallow fields, and bulldozed clearings of pine flatwoods. Associated species include Liatris pauciflora, Aristida, Sorghastrum, Carphephorus corymbosus, Pinus clausa, Serenoa repens, Carya florida, Quercus myrtifolia, Quercus geminata, Osmanthus megacarpus, Prunus geniculata, Bumelia, Ceranthera, Polygonella, and Penstemon.[5]

Phenology

Flowers and fruits August through December.[5] Herndon[4] observed that all of the flowers will produce seeds as long as they were not degraded by herbivores or pathogens.

Fire ecology

It has been observed to have a strong fire-dependent blooming behavior, blooming in large numbers in pinelands that have been burned recently, and rarely blooming or not at all in pinelands that have been unburned for more than two years.[6] Anderson and Menges[7] found that L. tenuifolia var. laevigata responded quickly and strongly to burning and blooms at high rates in the year following a fire. This study also found that concentrations of Nitrogen, Phosphorous, Potassium, and Iron were 2 to 6 fold higher in individuals in burned areas compared to those in unburned areas. The root length of individuals is also longer in burned sites.

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Liatris laevigata at Archbold Biological Station:[8]

Apidae: Bombus impatiens

Halictidae: Augochlorella aurata, Augochlorella gratiosa, Augochloropsis sumptuosa, Lasioglossum coreopsis

Megachilidae: Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, Megachile mendica

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ [[1]] Florida Native Wildflowers Accessed: January 12, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 [[2]] New Mexico Biodiversity Portal Accessed January 13, 2016

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Herndon, A. (1987). "Variation in Resource Allocation and Reproductive Effort within a Single Population of Liatris laevigata Nuttall (Asteraceae)." American Midland Naturalist 118(2): 406-413.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Jane Brockmann, W.C. Brumbach, Richard Carter, Steven P. Christman, Andre F. Clewell, George R. Cooley, David K. Dorman, Richard J. Eaton, J. Ferborgh, Robert K. Godfrey, S.C. Hood, Beverly Judd, Walter S. Judd, Gary R. Knight, Robert Kral, Olga Lakela, S.W. Leonard, Tin Myint, Jackie Patman, R.E. Perdue Jr., Kent D. Perkins, James D. Ray Jr., D.B. Ward. States and Counties: Florida: Brevard, Citrus, Collier, Dade, Duval, Hardee, Hernando, Highlands, Hillsborough, Jackson, Lake, Lee, Levy, Marion, Monroe, Nassau, Osceola, Pinellas, Polk, Putnam, St. Johns, Suwannee, Taylor. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Herndon A. 1987. Variation in Resource Allocation and Reproductive Effort within a Single Population of Liatris laevigata Nuttall (Asteraceae). The American Midland Naturalist. 118(2): 406-413.

- ↑ Anderson RC, Menges ES. 1997. Effects of Fire on Sandhill Herbs: Nutrients, Mycorrhizae, and Biomass Allocation. American Journal of Botany. 84(7): 938.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowering plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.