Difference between revisions of "Viola lanceolata"

(→Taxonomic Notes) |

(→Taxonomic Notes) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==Taxonomic Notes== | ==Taxonomic Notes== | ||

Varieties: ''V. lanceolata'' Linnaeus var. ''lanceolata''; ''V. lanceolata'' Linnaeus var. ''vittata'' (Greene) Weatherby & Griscom | Varieties: ''V. lanceolata'' Linnaeus var. ''lanceolata''; ''V. lanceolata'' Linnaeus var. ''vittata'' (Greene) Weatherby & Griscom | ||

| + | |||

Subspecies: ''V. lanceolata'' ssp. ''lanceolata''; ''V. lanceolata'' ssp. ''vittata''; ''V. lanceolata'' ssp. ''occidentalis''<ref name="USDA"/> | Subspecies: ''V. lanceolata'' ssp. ''lanceolata''; ''V. lanceolata'' ssp. ''vittata''; ''V. lanceolata'' ssp. ''occidentalis''<ref name="USDA"/> | ||

Revision as of 12:42, 29 June 2018

| Viola lanceolata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Hilty hosted at IllinoisWildflowers.info | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Violales |

| Family: | Violaceae |

| Genus: | Viola |

| Species: | V. lanceolata |

| Binomial name | |

| Viola lanceolata L. | |

| |

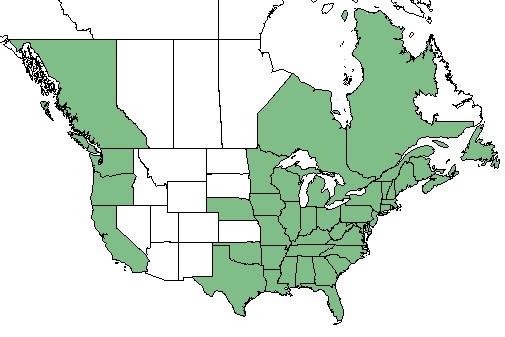

| Natural range of Viola lanceolata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Names: lanceleaf violet; narrow-leaved violet; strap-leaved violet;[1] bog white violet[2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Varieties: V. lanceolata Linnaeus var. lanceolata; V. lanceolata Linnaeus var. vittata (Greene) Weatherby & Griscom

Subspecies: V. lanceolata ssp. lanceolata; V. lanceolata ssp. vittata; V. lanceolata ssp. occidentalis[2]

Description

Viola lanceolata is a dioecious perennial forb/herb.[2] It is stemless and produces white flowers. Leaves are narrow, lanceolate, glabrous and held erect. V. lanceolata also produces long slender stolons, allowing established plants to vegetatively spread. The number of flowers produced are exponentially correlated with the number of leaves the plant has. In Massachusetts, seed capsules contained 44.1 seeds on average; these ranged from 16-68 seeds.[3] This species also hybridizes with other species of Viola including V. macloskeyi ssp. pallens.[4]

Distribution

This species occurs from New Brunswick, westward to Minnesota, and southward to Florida and eastern Texas.[1] There have also been reports along the Pacific coast in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

V. lanceolata is found in boggs, seepage slopes, pitcher plant seepage bogs, streamheads and their margins, small swamp forests, depression ponds, interdune swales and ponds, and other wet habitats.[1] This species also prefers more shady habitats than V. fimbriatula and was not observed in open areas in a Massachusetts study.[3] It also prefers wet sandy soils.[5] Despite this species close proximity to water, flooding produces a reduction in the number of germinations per core.[6] In Nova Scotia, Canada, this species occurs from the water line to ~0.5 m above it.[7][8]

Phenology

In the southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, flowering occurs from February through May.[1] On the Florida panhandle, flowering has been observed from November through May, peaking in March and April.[9] Its characteristic chasmogamous flowers are produced from June to September and die with the first frost in Massachusetts. This species will overwinter as stolons or short underground stems until a new growth period is triggered by warming temperatures. Growth occurs from April to late August or September, peaking in late August.[3]

Seed bank and germination

At an Ontario lake, the frequency of V. lanceolata was 97 at 0.2-0.8 m below the maximum water level and 100 and 13 at 0.8-1.3 m and 1.3-1.5 m, respectively. The mean number of collected seeds that germinated from this lake was 17.4 seeds dm-2.[10] In Massachusetts, seed densities ranged between 1,415-6,723 seeds m-2, peaking in the summer after seed dispersal and being lowest in the spring after seed germination. Ants will transport seed to their nests which may explain the observed clumped distribution of seeds. Between 1977 and 1979, 0-40 seedlings m-2 emerged in permanent Massachusetts study quadrats[3] A greenhouse study showed V. lanceolata has higher germination rates (~20%) when 5 cm above the water line and that seedlings. However, on axe lake in Ontario, the species is found around 28 cm above the water line.[11]

Pollination

It produces chasmogamous flowers,[3] that when open, allow easy access to pollen by biotic and abiotic pollinators.

Use by animals

Survivorship in Massachusetts seedlings have been reported at 0.60 and 0.82 where mortality was caused by wilting (74%), herbivory (10%), and unknown causes (16%). Slugs, field mice, and deer may contribute to the loss of leaves.[3]

Diseases and parasites

Leaves can be attacked by fungi.[3]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 05 February 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Solbrig OT, Curtis WF, Kincaid DT, Newell SJ (1988) Studies on the population biology of the genus Viola. VI. The demography of V. Fimbriatula and V. Lanceolata. Journal of Ecology 76(2):301-319.

- ↑ Russell NH (1954) Three field studies of hybridization in the stemless white violets. American Journal of Botany 41(8):679-686.

- ↑ Ranua VA, Weinig C (2010) Mixed-mating strategies and their sensitivity to abiotic variation in Viola lanceolata L. (Violaceae). The Open Ecology Journal 3:83-94.

- ↑ Schneider R (1994) The role of hydrologic regime in maintaining rare plant communities of New York's coastal plain pondshores. Biological Conservation 68:253-260.

- ↑ Keddy PA (1984) Plant zonation on lakeshores in Nova Scotia: A test of the resource specialization hypothesis. Journal of Ecology 72(3):797-808.

- ↑ Keddy PA, Wisheu IC (1989) Ecology, biogeography, and conservation of coastal plain plants: Some general principles from the study of Nova Scotian wetlands. Rhodora 91(865):72-94.

- ↑ Nelson G (05 February 2018) PanFlora. Retrieved from gilnelson.com/PanFlora/

- ↑ Keddy PA, Reznicek AA (1982) The role of seed banks in the persistence of Ontario's coastal plain flora. American Journal of Botany 69(1):13-22.

- ↑ Moore DRJ, Keddy PA (1988) Effects of a water-depth gradient on the germination of lakeshore plants. Canadian Journal of Botany 66:548-552.