Difference between revisions of "Erythrina herbacea"

(→Pollination and use by animals) |

Adam.Vansant (talk | contribs) |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Common names: | + | Common names: redcardinal, coral bean, Cherokee bean, cardinal-spear, colorin |

==Taxonomic notes== | ==Taxonomic notes== | ||

| − | Synonyms: | + | Synonyms: none<ref name=weakley>Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> |

| − | Varieties: | + | Varieties: ''Erythrina arborea'' (Chapman) Small<ref name=weakley/> |

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

The root system of ''Erythrina herbacea'' includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 338 mg/g (ranking 11 out of 100 species studied).<ref name = "Diaz"/> | The root system of ''Erythrina herbacea'' includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 338 mg/g (ranking 11 out of 100 species studied).<ref name = "Diaz"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), ''Erythrina herbacea'' has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.393 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 338 mg g<sup>-1</sup>.<ref>Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.</ref> | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| − | This species is generally distributed from southeast North Carolina south to Florida, west to southeast Texas, and south into eastern Mexico.<ref name= | + | This species is generally distributed from southeast North Carolina south to Florida, west to southeast Texas, and south into eastern Mexico.<ref name=weakley/> |

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | General habitats of ''E. herbacea'' includes dry sandy woodlands, maritime forests, and sandhills within the outer Coastal Plain region.<ref name= | + | General habitats of ''E. herbacea'' includes dry sandy woodlands, maritime forests, and sandhills within the outer Coastal Plain region.<ref name=weakley/> It occurs in sand pine woodlands, sandy hills, along edges of sinkholes, live oak-cabbage palm forests, uplands, hammocks, flatwoods, sand pine scrub, pine-palmetto scrub near ocean, longleaf pine-wiregrass savannas, shaded slopes of river bluffs, and in calcareous open prairies. Found in disturbed areas such as along roadsides, in understory of recently clear cut pine woodlands, and edges of woodlands. Can thrive in areas that are shady, semi-shady, or open. Is associated with areas that have sand soil types, sandy loam, loam, thin loamy sand, and calcareous soil types.<ref name=fsu>Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: D. B. Ward, G. Crosby, R. Kral, George R. Cooley, Carroll E. Wood, Jr., Kenneth A. Wilson, R.K. Godfrey, Grady W. Reinert, James D. Ray, Jr., C. E. Smith, Olga Lakela, Jackie Patman, Richard J. Eaton, Richard S. Mitchell, Tom Barnes, C. Jackson, A. F. Clewell, Loran C. Anderson, Gary R. Knight, K. Craddock Burks, S. W. Leonard, Elbert L. Little, Jr., Robert J Lemaire, Jack P. Davis, Rodie White, Wilson Baker, R. Komarek, Lisa Keppner, Annie Schmidt, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, Tim Clemons, R. L. Wilbur, C. Ritchie Bell, Samuel B. Jones, Nancy Coile, et al., Roomie Wilson, Clarke Hudson, Sidney McDaniel, and A Traverse. States and Counties: Florida: Brevard, Calhoun, Citrus, Collier, Dade, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hardee, Indian River, Jackson, Leon, Liberty, Marion, Okaloosa, Pasco, Pinellas, St Lucie, Suwannee, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Grady and McIntosh. Louisiana: Hammond. Mississippi: Adams, Jasper, and Kemper. South Carolina: Berkeley and Horry. Texas: Harris.</ref> It is also considered an indicator species of the north Florida longleaf woodlands, and a characteristic species of the shortleaf pine-oak-hickory community type in the Red Hills region of north Florida and south Georgia.<ref name= "Carr">Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.</ref><ref>Clewell, A. F. (2013). "Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills." Castanea 78(4): 266-276.</ref> ''E. herbacea'' was found to increase its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture. It has shown regrowth in reestablished native habitat that was disturbed by agricultural practices in southwest Georgia.<ref>Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.</ref> ''E. herbacea'' exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.<ref>McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.</ref> additionally, it was to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.<ref name=Dixon>Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.</ref> |

Associated species include ''Quercus geminata, Q. chapmanii, Q. incana, Osmanthus megacarpus, Ilex ambigua, Vitis rotundifolia, Serenoa repens, Persea, Myrica, Carya glabra'' var. ''megacarpa, Pinus palutris, Baccharis halimifolia, Rhus copalina, Callicarpa americana, Diospyros virginiana, Morus.''<ref name=fsu/> | Associated species include ''Quercus geminata, Q. chapmanii, Q. incana, Osmanthus megacarpus, Ilex ambigua, Vitis rotundifolia, Serenoa repens, Persea, Myrica, Carya glabra'' var. ''megacarpa, Pinus palutris, Baccharis halimifolia, Rhus copalina, Callicarpa americana, Diospyros virginiana, Morus.''<ref name=fsu/> | ||

| Line 42: | Line 44: | ||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| − | ''E. herbacea'' generally flowers from May until July.<ref name= | + | ''E. herbacea'' generally flowers from May until July.<ref name=weakley/> It has been observed flowering from February to June with peak inflorescence in April and May, and fruiting from April to August.<ref name=fsu/><ref>Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 10 MAY 2019</ref> |

| + | |||

<!--===Seed dispersal===--> | <!--===Seed dispersal===--> | ||

| Line 51: | Line 54: | ||

Is associated with annually burned pinelands.<ref name=fsu/> | Is associated with annually burned pinelands.<ref name=fsu/> | ||

| − | ===Pollination | + | ===Pollination=== |

| − | Hummingbirds drink the nectar and pollinate ''E. herbacea''.<ref name= "lady bird"/> ''E. herbacea'' is a food source seldom used by white-tailed deer as well as an introduced population of fallow deer in Georgia.<ref>Harlow, R. F. (1961). "Fall and winter foods of Florida white-tailed deer." The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 24(1): 19-38.</ref><ref>Morse, B. W., et al. (2009). "Seasonal Diets of an Introduced Population of Fallow Deer on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia." Southeastern Naturalist 8(4): 571-586.</ref> | + | Hummingbirds drink the nectar and pollinate ''E. herbacea''.<ref name= "lady bird"/> |

| + | |||

| + | ===Herbivory and toxicology=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''E. herbacea'' is a food source seldom used by white-tailed deer as well as an introduced population of fallow deer in Georgia.<ref>Harlow, R. F. (1961). "Fall and winter foods of Florida white-tailed deer." The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 24(1): 19-38.</ref><ref>Morse, B. W., et al. (2009). "Seasonal Diets of an Introduced Population of Fallow Deer on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia." Southeastern Naturalist 8(4): 571-586.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

Latest revision as of 12:09, 2 August 2024

| Erythrina herbacea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Erythrina |

| Species: | E. herbacea |

| Binomial name | |

| Erythrina herbacea L. | |

| |

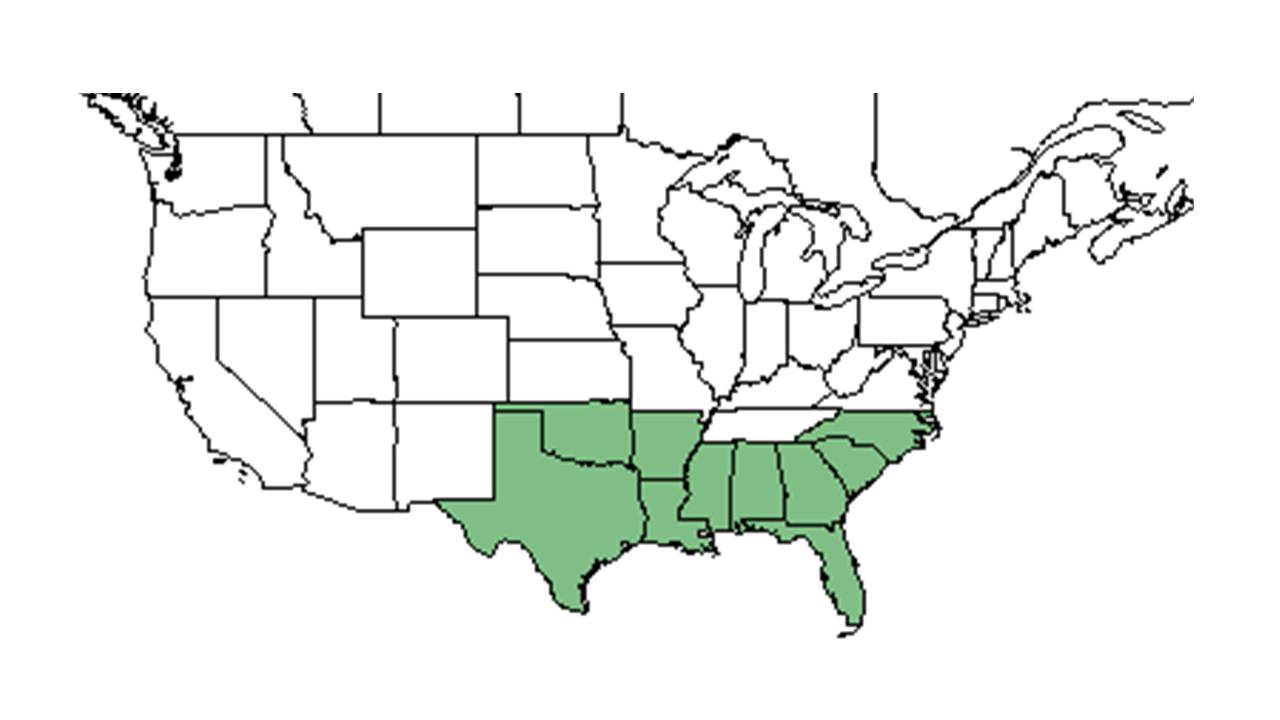

| Natural range of Erythrina herbacea from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: redcardinal, coral bean, Cherokee bean, cardinal-spear, colorin

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: Erythrina arborea (Chapman) Small[1]

Description

"Perennial herb, 0.6-1.2 m tall (or shrub or tree up to 8 m high further south) with usually prickly brachlets. Leaves pinnately 3-foliolate; leatlets thinly chartaceous, glabrous, or nearly so, throughout, occasionally pricky beneath, hastately 3-lobed to widely deltoid, (2) 4-8 (12) cm long, stipellate. Inflorescence terminal, much elongate on usually leafless stems arising from the crown, (1) 3-7 dm long with few to numerous, papilionaceous flowers; pedicels 3-9 mm long, subtended by linear- lanceolate bracts 1-4 mm long and with 2 liner, caduceus bractlets, 1-2 mm long. Calyx glabrous, or nearly so, tubecampanulate, truncate, 5-11 mm long; the standard scarlet, 3-5.3 cm long, wings 5.5-11 mm long, keel 6-13 mm long; stamens diadelphous, 9 and 1; stigma capitate, ovary and stipe pubescent. Legume 7-15 (21) cm long, 1.2-1.6 cm broad, constricted between the several to many, scarlet seeds, stipe 1.5-4.5 cm long." [2]

The root system of Erythrina herbacea includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 338 mg/g (ranking 11 out of 100 species studied).[3]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Erythrina herbacea has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.393 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 338 mg g-1.[4]

Distribution

This species is generally distributed from southeast North Carolina south to Florida, west to southeast Texas, and south into eastern Mexico.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

General habitats of E. herbacea includes dry sandy woodlands, maritime forests, and sandhills within the outer Coastal Plain region.[1] It occurs in sand pine woodlands, sandy hills, along edges of sinkholes, live oak-cabbage palm forests, uplands, hammocks, flatwoods, sand pine scrub, pine-palmetto scrub near ocean, longleaf pine-wiregrass savannas, shaded slopes of river bluffs, and in calcareous open prairies. Found in disturbed areas such as along roadsides, in understory of recently clear cut pine woodlands, and edges of woodlands. Can thrive in areas that are shady, semi-shady, or open. Is associated with areas that have sand soil types, sandy loam, loam, thin loamy sand, and calcareous soil types.[5] It is also considered an indicator species of the north Florida longleaf woodlands, and a characteristic species of the shortleaf pine-oak-hickory community type in the Red Hills region of north Florida and south Georgia.[6][7] E. herbacea was found to increase its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture. It has shown regrowth in reestablished native habitat that was disturbed by agricultural practices in southwest Georgia.[8] E. herbacea exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[9] additionally, it was to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[10]

Associated species include Quercus geminata, Q. chapmanii, Q. incana, Osmanthus megacarpus, Ilex ambigua, Vitis rotundifolia, Serenoa repens, Persea, Myrica, Carya glabra var. megacarpa, Pinus palutris, Baccharis halimifolia, Rhus copalina, Callicarpa americana, Diospyros virginiana, Morus.[5]

Erythrina herbacea is an indicator species for the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Phenology

E. herbacea generally flowers from May until July.[1] It has been observed flowering from February to June with peak inflorescence in April and May, and fruiting from April to August.[5][12]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds germinate easily when scarified.[13]

Fire ecology

Is associated with annually burned pinelands.[5]

Pollination

Hummingbirds drink the nectar and pollinate E. herbacea.[13]

Herbivory and toxicology

E. herbacea is a food source seldom used by white-tailed deer as well as an introduced population of fallow deer in Georgia.[14][15]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

For general management, dead stem tips should be trimmed once new growth emerges in the spring when frost damage is visible.[13]

Cultural use

This species has toxic seeds for humans, which are used in Mexico for poisoning rats and various fish; the seeds are also made into novelties and necklaces which should be kept away from children.[13] The root of this plant has also been used medicinally as an expectorant, a sudorific, and a febrifuge.[16]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 634. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: D. B. Ward, G. Crosby, R. Kral, George R. Cooley, Carroll E. Wood, Jr., Kenneth A. Wilson, R.K. Godfrey, Grady W. Reinert, James D. Ray, Jr., C. E. Smith, Olga Lakela, Jackie Patman, Richard J. Eaton, Richard S. Mitchell, Tom Barnes, C. Jackson, A. F. Clewell, Loran C. Anderson, Gary R. Knight, K. Craddock Burks, S. W. Leonard, Elbert L. Little, Jr., Robert J Lemaire, Jack P. Davis, Rodie White, Wilson Baker, R. Komarek, Lisa Keppner, Annie Schmidt, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, Tim Clemons, R. L. Wilbur, C. Ritchie Bell, Samuel B. Jones, Nancy Coile, et al., Roomie Wilson, Clarke Hudson, Sidney McDaniel, and A Traverse. States and Counties: Florida: Brevard, Calhoun, Citrus, Collier, Dade, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hardee, Indian River, Jackson, Leon, Liberty, Marion, Okaloosa, Pasco, Pinellas, St Lucie, Suwannee, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Grady and McIntosh. Louisiana: Hammond. Mississippi: Adams, Jasper, and Kemper. South Carolina: Berkeley and Horry. Texas: Harris.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2013). "Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills." Castanea 78(4): 266-276.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 10 MAY 2019

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 10, 2019

- ↑ Harlow, R. F. (1961). "Fall and winter foods of Florida white-tailed deer." The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 24(1): 19-38.

- ↑ Morse, B. W., et al. (2009). "Seasonal Diets of an Introduced Population of Fallow Deer on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia." Southeastern Naturalist 8(4): 571-586.

- ↑ Nickell, J. M. (1911). J.M.Nickell's botanical ready reference : especially designed for druggists and physicians : containing all of the botanical drugs known up to the present time, giving their medical properties, and all of their botanical, common, pharmacopoeal and German common (in German) names. Chicago, IL, Murray & Nickell MFG. Co.