Difference between revisions of "Elephantopus tomentosus"

Adam.Vansant (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Common name: | + | Common name: devil's grandmother; common elephant's-foot |

==Taxonomic notes== | ==Taxonomic notes== | ||

| − | Synonyms: none | + | Synonyms: none<ref name=weakley>Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> |

| − | Varieties: none | + | Varieties: none<ref name=weakley/> |

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| − | ''E. tomentosus'' is native to the southeastern Coastal Plain from Maryland south to the Florida panhandle, west to eastern Texas and Arkansas, and north up to western North Carolina and Kentucky. It is also native south of the United States to Chiapas, Mexico.<ref name= | + | ''E. tomentosus'' is native to the southeastern Coastal Plain from Maryland south to the Florida panhandle, west to eastern Texas and Arkansas, and north up to western North Carolina and Kentucky. It is also native south of the United States to Chiapas, Mexico.<ref name=weakley/> |

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | Generally, this species can be found in | + | Generally, this species can be found in fairly dry woodlands and woodland borders.<ref name=weakley/> It has been observed in mixed woodlands, pine-hardwoods, edges of mixed hardwoods, in deciduous woodlands along river bluff, edges of rivers, longleaf pine-Turkey oak woods, open pinelands, and dry upland pine woodlands. Is also found in human disturbed areas such as roadsides and areas that have been clear cut. A study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found ''E. tomentosus'' to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 90-180 years of age.<ref>Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.</ref> This species is associated with areas that have dry, loamy sand and sand soil types.<ref name=fsu>Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, James R. Burkhalter, Robert K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, Wilson Baker, Paul L. Redfearn, Jr., Richard S. Mitchell, John C. Ogden, Cecil R Slaughter, R. Komarek, R. A. Norris, and J. M. Kane. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Escambia, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Thomas.</ref> It also grows in pine-oak-hickory forest communities and lake shores.<ref>Bostick, P. E. (1971). "Vascular Plants of Panola Mountian, Georgia " Castanea 46(3): 194-209.</ref> One study in Mississippi found this species to be present in nondisturbed areas as well as disturbed areas by tornadoes, making it a perannial disturbance indicator.<ref>Brewer, S. J., et al. (2012). "Do natural disturbances or the forestry practices that follow them convert forests to early-successional communities?" Ecological Applications 22: 442-458.</ref> |

| − | ''E. tomentosus'' became absent in response to soil disturbance by military training in west Georgia. It has also shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine forests that were disturbed by this training.<ref name=dale>Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.</ref> However, it was found to increase in frequency in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests. It has shown positive regrowth in reestablished flatwood habitat that was disturbed by these practices.<ref name=moore>Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.</ref> | + | ''E. tomentosus'' became absent in response to soil disturbance by military training in west Georgia. It has also shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine forests that were disturbed by this training.<ref name=dale>Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.</ref> However, it was found to increase in frequency in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests. It has shown positive regrowth in reestablished flatwood habitat that was disturbed by these practices.<ref name=moore>Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.</ref> ''E. tomoatosa'' was found to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances.<ref name=Dixon>Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.</ref> |

Associated species include ''Sericocarpus asteroids, Eupatorium album, E. perfoliatum, E. rotundifolium, Solidago rugosa, Helianthus strumosus.''<ref name=fsu/> | Associated species include ''Sericocarpus asteroids, Eupatorium album, E. perfoliatum, E. rotundifolium, Solidago rugosa, Helianthus strumosus.''<ref name=fsu/> | ||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| − | ''E. tomentosus'' generally flowers from August to November.<ref name= | + | ''E. tomentosus'' generally flowers from August to November.<ref name=weakley/> It has been observed flowering from April through October.<ref name=fsu/><ref>Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 6 MAY 2019</ref> |

<!--===Seed dispersal===--> | <!--===Seed dispersal===--> | ||

<!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | <!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

It is found in areas that are annually burned, such as longleaf pine terrain.<ref name=fsu/> Frequency of this species has been shown to significantly increase in areas that prescribed fire is used.<ref>Moore, W. H., et al. (1982). "Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest." Journal of Range Management 35: 386-389.</ref> A study on seasonality of fire found ''E. tomentosus'' to benefit most and have highest frequency in response to winter and spring burns rather than summer burns.<ref>Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.</ref> | It is found in areas that are annually burned, such as longleaf pine terrain.<ref name=fsu/> Frequency of this species has been shown to significantly increase in areas that prescribed fire is used.<ref>Moore, W. H., et al. (1982). "Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest." Journal of Range Management 35: 386-389.</ref> A study on seasonality of fire found ''E. tomentosus'' to benefit most and have highest frequency in response to winter and spring burns rather than summer burns.<ref>Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.</ref> | ||

| − | ===Pollination and | + | <!--===Pollination===--> |

| + | |||

| + | ===Herbivory and toxicology=== <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

''Elephantopus tomentosus'' consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals.<ref>Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> ''E. tomentosus'' is considered to have fair forage value.<ref>Hilman, J. B. (1964). "Plants of the Caloosa Experimental Range " U.S. Forest Service Research Paper SE-12 </ref> | ''Elephantopus tomentosus'' consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals.<ref>Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> ''E. tomentosus'' is considered to have fair forage value.<ref>Hilman, J. B. (1964). "Plants of the Caloosa Experimental Range " U.S. Forest Service Research Paper SE-12 </ref> | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== | ||

| − | This species is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Natural Heritage Program.<ref name= "USDA">USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 6 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.</ref> | + | ''E. tomentosus'' should avoid soil disturbance by military training to conserve its presence in pine communities.<ref name=dale/> This species is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Natural Heritage Program.<ref name= "USDA">USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 6 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.</ref> |

==Cultural use== | ==Cultural use== | ||

Latest revision as of 19:56, 1 August 2024

| Elephantopus tomentosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Elephantopus |

| Species: | E. tomentosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Elephantopus tomentosus L. | |

| |

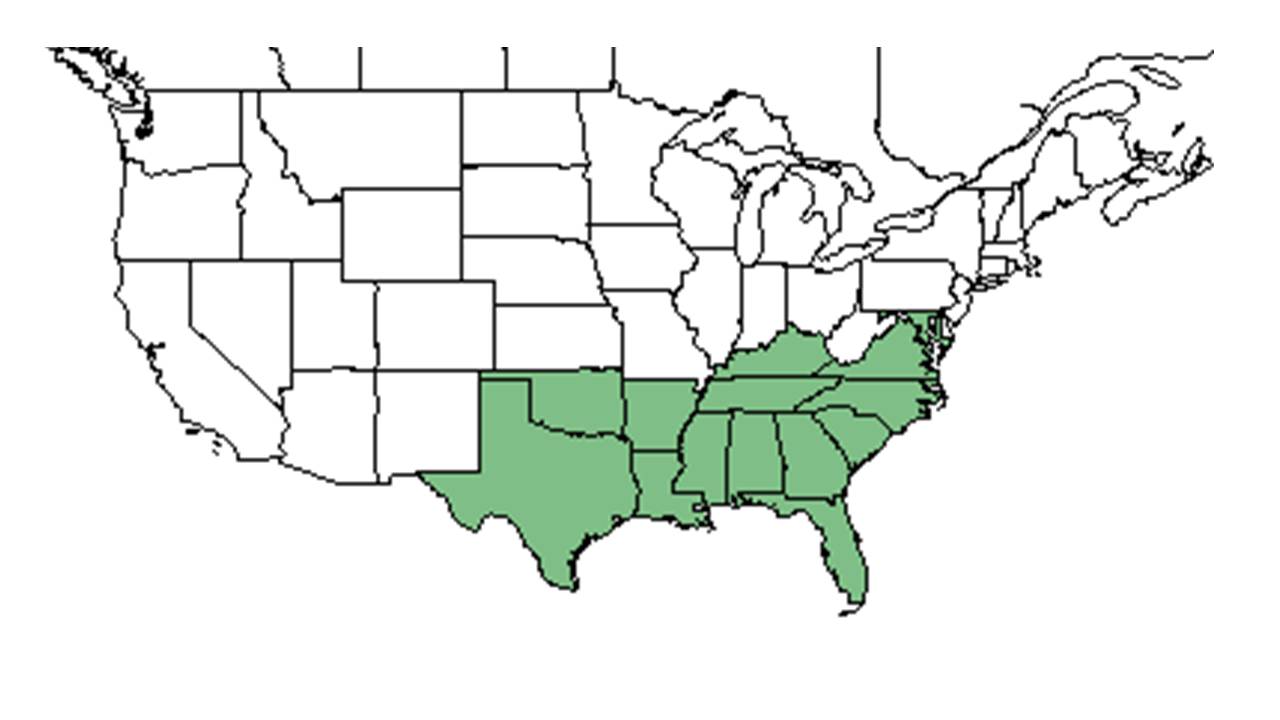

| Natural range of Elephantopus tomentosus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: devil's grandmother; common elephant's-foot

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Elephantopus tomentosus is provided in The Flora of North America. It reaches a height of about 2 feet with flowers ranging in color from pink to purple as well as rarely white.[2]

Distribution

E. tomentosus is native to the southeastern Coastal Plain from Maryland south to the Florida panhandle, west to eastern Texas and Arkansas, and north up to western North Carolina and Kentucky. It is also native south of the United States to Chiapas, Mexico.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, this species can be found in fairly dry woodlands and woodland borders.[1] It has been observed in mixed woodlands, pine-hardwoods, edges of mixed hardwoods, in deciduous woodlands along river bluff, edges of rivers, longleaf pine-Turkey oak woods, open pinelands, and dry upland pine woodlands. Is also found in human disturbed areas such as roadsides and areas that have been clear cut. A study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found E. tomentosus to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 90-180 years of age.[3] This species is associated with areas that have dry, loamy sand and sand soil types.[4] It also grows in pine-oak-hickory forest communities and lake shores.[5] One study in Mississippi found this species to be present in nondisturbed areas as well as disturbed areas by tornadoes, making it a perannial disturbance indicator.[6]

E. tomentosus became absent in response to soil disturbance by military training in west Georgia. It has also shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine forests that were disturbed by this training.[7] However, it was found to increase in frequency in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests. It has shown positive regrowth in reestablished flatwood habitat that was disturbed by these practices.[8] E. tomoatosa was found to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances.[9]

Associated species include Sericocarpus asteroids, Eupatorium album, E. perfoliatum, E. rotundifolium, Solidago rugosa, Helianthus strumosus.[4]

Phenology

E. tomentosus generally flowers from August to November.[1] It has been observed flowering from April through October.[4][10]

Fire ecology

It is found in areas that are annually burned, such as longleaf pine terrain.[4] Frequency of this species has been shown to significantly increase in areas that prescribed fire is used.[11] A study on seasonality of fire found E. tomentosus to benefit most and have highest frequency in response to winter and spring burns rather than summer burns.[12]

Herbivory and toxicology

Elephantopus tomentosus consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals.[13] E. tomentosus is considered to have fair forage value.[14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

E. tomentosus should avoid soil disturbance by military training to conserve its presence in pine communities.[7] This species is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Natural Heritage Program.[15]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 6, 2019

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, James R. Burkhalter, Robert K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, Wilson Baker, Paul L. Redfearn, Jr., Richard S. Mitchell, John C. Ogden, Cecil R Slaughter, R. Komarek, R. A. Norris, and J. M. Kane. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Escambia, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ Bostick, P. E. (1971). "Vascular Plants of Panola Mountian, Georgia " Castanea 46(3): 194-209.

- ↑ Brewer, S. J., et al. (2012). "Do natural disturbances or the forestry practices that follow them convert forests to early-successional communities?" Ecological Applications 22: 442-458.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 6 MAY 2019

- ↑ Moore, W. H., et al. (1982). "Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest." Journal of Range Management 35: 386-389.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Hilman, J. B. (1964). "Plants of the Caloosa Experimental Range " U.S. Forest Service Research Paper SE-12

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 6 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.