Difference between revisions of "Desmodium strictum"

(→Taxonomic notes) |

Adam.Vansant (talk | contribs) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

The root system of ''D.strictum'' includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 70.1 mg/g (ranking 62 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 48.8% (ranking 64 out of 100 species studied).<ref name = "Diaz"/> | The root system of ''D.strictum'' includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 70.1 mg/g (ranking 62 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 48.8% (ranking 64 out of 100 species studied).<ref name = "Diaz"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), ''Desmodium strictum'' has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 1.84 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 70.1 mg g<sup>-1</sup>.<ref>Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.</ref> | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| Line 37: | Line 39: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | Generally, ''D. strictum'' can be found in dry woodlands and sandhills.<ref name= "Weakley"/> It thrives in open, frequently burned areas such as longleaf pine and shortleaf pine old field habitats (ultisols). <ref name=cof> Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299. </ref> <ref name=fsu> Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, R. K. Godfrey, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, James R. Ray Jr., John Morrill, Robert L. Lazor, Andre F. Clewell, and T. MacClendon. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Bradford, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Jackson, Leon, Putnam, Taylor, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Baker, Grady, and Thomas.</ref> It also occurs in longleaf pine-turkey oak sandhills (entisols), and in longleaf pine and slash pine flatwoods (spodosols).<ref name=fsu/> It occurs in habitats dominated by ultisol soil types with average temperatures from 11 to 27° Celsuis, and with 132 cm of annual rainfall. <ref name=cof/> In florida, ''D. strictum'' is an indicator species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands community.<ref>Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.</ref> It is seen in habitats with soil types of sandy loam to eroded sandy clayey areas. <ref name=fsu/> It prefers to grow in either partial shade or full shade.<ref>[[https://www.wildflower.org/plants/search.php?search_field=&newsearch=true]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 26, 2019</ref> Outside of the southeast coastal plain, ''D. strictum'' can be found in upland pitch pine barrens in New Jersey.<ref>[[http://explorer.natureserve.org/]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: April 26, 2019</ref> ''D. strictum'' was found to increase in occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina. It has also shown positive regrowth in reestablished native longleaf pinelands, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> ''D. strictum'' was found to have variable changes in density in response to roller chopping in northwest Florida sandhills. It has shown either positive regrowth or no change in regrowth in reestablished native sandhill habitat that was disturbed by roller chopping.<ref>Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.</ref> | + | Generally, ''D. strictum'' can be found in dry woodlands and sandhills.<ref name= "Weakley"/> It thrives in open, frequently burned areas such as longleaf pine and shortleaf pine old field habitats (ultisols). <ref name=cof> Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299. </ref> <ref name=fsu> Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, R. K. Godfrey, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, James R. Ray Jr., John Morrill, Robert L. Lazor, Andre F. Clewell, and T. MacClendon. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Bradford, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Jackson, Leon, Putnam, Taylor, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Baker, Grady, and Thomas.</ref> It also occurs in longleaf pine-turkey oak sandhills (entisols), and in longleaf pine and slash pine flatwoods (spodosols).<ref name=fsu/> It occurs in habitats dominated by ultisol soil types with average temperatures from 11 to 27° Celsuis, and with 132 cm of annual rainfall. <ref name=cof/> In florida, ''D. strictum'' is an indicator species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands community.<ref>Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.</ref> It is seen in habitats with soil types of sandy loam to eroded sandy clayey areas. <ref name=fsu/> It prefers to grow in either partial shade or full shade.<ref>[[https://www.wildflower.org/plants/search.php?search_field=&newsearch=true]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 26, 2019</ref> Outside of the southeast coastal plain, ''D. strictum'' can be found in upland pitch pine barrens in New Jersey.<ref>[[http://explorer.natureserve.org/]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: April 26, 2019</ref> ''D. strictum'' was found to increase in occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina. It has also shown positive regrowth in reestablished native longleaf pinelands, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> ''D. strictum'' was found to have variable changes in density in response to roller chopping in northwest Florida sandhills. It has shown either positive regrowth or no change in regrowth in reestablished native sandhill habitat that was disturbed by roller chopping.<ref>Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.</ref> ''D. strictum'' was found to be neutral in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances but an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.<ref name=Dixon>Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.</ref> |

Associated species include ''D. viridiflorum, D. floridanum, D. glabellum, D. canescens, D. marilandicum, Aristida stricta, Pinus palutris,'' and ''P. elliotii''. <ref name=fsu/> | Associated species include ''D. viridiflorum, D. floridanum, D. glabellum, D. canescens, D. marilandicum, Aristida stricta, Pinus palutris,'' and ''P. elliotii''. <ref name=fsu/> | ||

Latest revision as of 18:16, 1 August 2024

| Desmodium strictum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. strictum |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium strictum (Pursh) DC. | |

| |

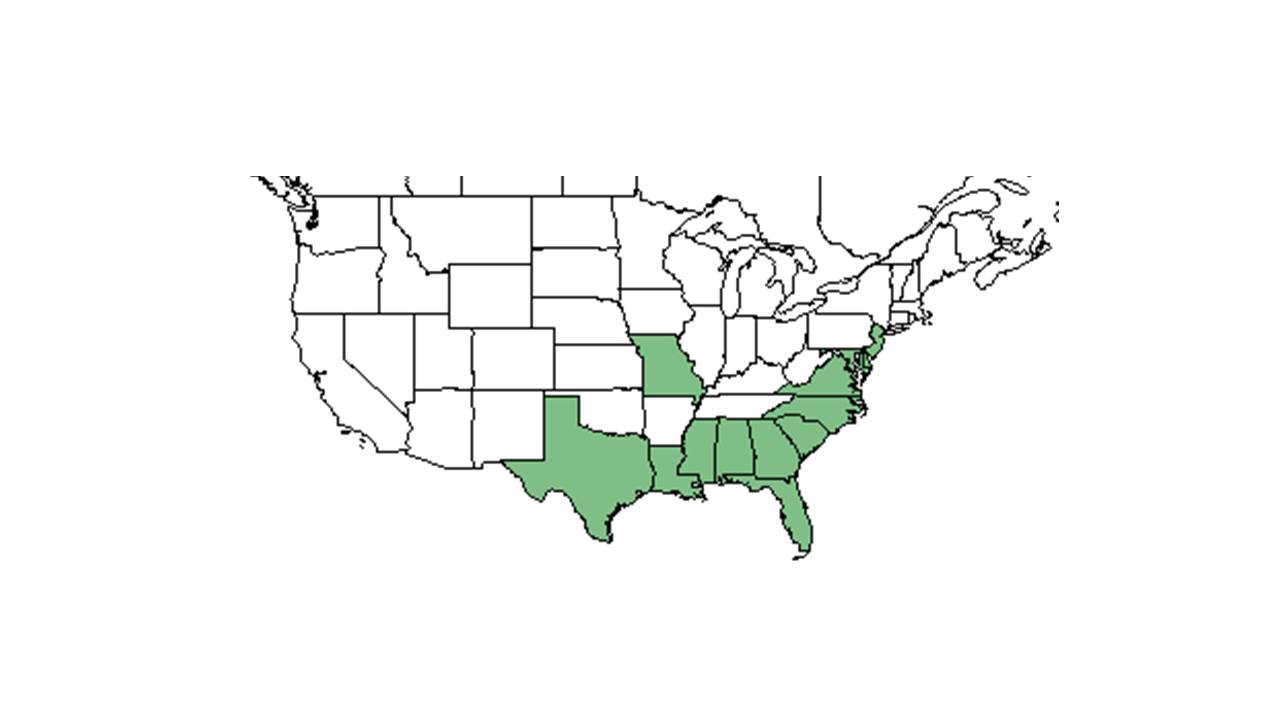

| Natural range of Desmodium strictum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: pinebarren tick-trefoil; pineland tick-trefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Meibomia stricta (Pursh) Kuntze[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

Generally, for Desmodium genus, they are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments." [2]

Specifically, for D.strictum species, they are "erect perennial; stems 0.5-1.2 m tall, sparsely to densely uncinulate-puberulent and short-pubescent, often becoming glabrate below. Terminal leaflets linear to narrowly oblong, often 6-10 X as long as wide, 3-7 cm long, glabrate or minutely puberulent or sparsely short-pubescent especially along the veins beneath, fine reticulate; stipules linear-subulate, 2-4 mm long; stipels persistent. Inflorescence usually paniculate, densely uncinulate-puberulent; pedicels (4) 6-11 mm long. Calyx densely puberulent and sparsely short-pubescent; petals purplish, 3-5 mm long, stamens diadelphous. Loments of 1-3 suborbicular to weakly obovate segments, each 4-6 mm long, 3-4 mm broad, upper suture of each segment slightly concave or indented, densely uncinlate-puberulent on both sutures and sides; stipe 1-2 mm long, about as long as calyx but shorter than stamina remnants." [2]

The root system of D.strictum includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 70.1 mg/g (ranking 62 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 48.8% (ranking 64 out of 100 species studied).[3]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Desmodium strictum has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 1.84 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 70.1 mg g-1.[4]

Distribution

D. strictum is native to the United States from south New Jersey down to south Florida and west to western Louisiana.[5]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, D. strictum can be found in dry woodlands and sandhills.[5] It thrives in open, frequently burned areas such as longleaf pine and shortleaf pine old field habitats (ultisols). [6] [7] It also occurs in longleaf pine-turkey oak sandhills (entisols), and in longleaf pine and slash pine flatwoods (spodosols).[7] It occurs in habitats dominated by ultisol soil types with average temperatures from 11 to 27° Celsuis, and with 132 cm of annual rainfall. [6] In florida, D. strictum is an indicator species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands community.[8] It is seen in habitats with soil types of sandy loam to eroded sandy clayey areas. [7] It prefers to grow in either partial shade or full shade.[9] Outside of the southeast coastal plain, D. strictum can be found in upland pitch pine barrens in New Jersey.[10] D. strictum was found to increase in occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina. It has also shown positive regrowth in reestablished native longleaf pinelands, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.[11][12] D. strictum was found to have variable changes in density in response to roller chopping in northwest Florida sandhills. It has shown either positive regrowth or no change in regrowth in reestablished native sandhill habitat that was disturbed by roller chopping.[13] D. strictum was found to be neutral in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances but an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[14]

Associated species include D. viridiflorum, D. floridanum, D. glabellum, D. canescens, D. marilandicum, Aristida stricta, Pinus palutris, and P. elliotii. [7]

Desmodium strictum is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[15]

Phenology

D. strictum generally flowers from July through August and fruits from August through October.[5] It has been observed to flower from September to October with peak inflorescence in October, and fruit from September to November.[16][7]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [17]

Seed bank and germination

Because Desmodium strictum lacks a hard seed coat, is not capable of forming long-term persistent seed banks, and rather germinates readily within one year following dispersal.[6]

Fire ecology

Populations of Desmodium strictum have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[18] and thrives in frequently burned (1-2 year interval) habitats.[6][7] Frequency of D. strictum is the greatest in response to winter and spring burn regiments rather than summer burn regiments.[19]

Pollination

Desmodium strictum has been observed to host leafcutting bees such as Anthidiellum notatum (family Megachilidae).[20]

Herbivory and toxicology

This species consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.[21]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. strictum is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.[22]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-9. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, R. K. Godfrey, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, James R. Ray Jr., John Morrill, Robert L. Lazor, Andre F. Clewell, and T. MacClendon. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Bradford, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Jackson, Leon, Putnam, Taylor, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Baker, Grady, and Thomas.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 26, 2019

- ↑ [[2]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: April 26, 2019

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 26 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [3]

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.