Difference between revisions of "Desmodium lineatum"

Adam.Vansant (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Common name: | + | Common name: sand tick-trefoil, matted tick-trefoil |

==Taxonomic notes== | ==Taxonomic notes== | ||

| − | Synonyms: | + | Synonyms: none<ref name=weakley>Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> |

| − | Varieties: | + | Varieties: ''Meibomia arenicola'' Vail; ''Meibomia polymorpha'' (A. Gray) Small<ref name=weakley/> |

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| − | Found in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. <ref name= "NRCS Plants Database">NRCS Plants Database http://plants.usda.gov/java/</ref> It is primarily found in the panhandle and upper peninsular of Florida. <ref name= "ISB Plants Database">ISB Plants Database http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/</ref> It is rarely found inland.<ref name= | + | Found in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. <ref name= "NRCS Plants Database">NRCS Plants Database http://plants.usda.gov/java/</ref> It is primarily found in the panhandle and upper peninsular of Florida. <ref name= "ISB Plants Database">ISB Plants Database http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/</ref> It is rarely found inland.<ref name=weakley/> |

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | ''D. lineatum'' is commonly found in sandhills as well as other dry woodlands and forests.<ref name= | + | ''D. lineatum'' is commonly found in sandhills as well as other dry woodlands and forests.<ref name=weakley/> It is found in frequently burned upland longleaf and shortleaf pine native and old-field communities (Ultisols),<ref name=brewer>Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle (2003). "Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (Imperata cylindrica)." Plant Ecology 167: 237-245.</ref><ref name=fsu/> pine-oak sandhills (Entisols), pine flatwoods (Spodosols), and open areas within upland hardwood forests. Thrives in frequently burned (1-2 year fire interval) areas (Gilliam et al 2009).<ref name=fsu/> ''D. lineatum'' is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> A study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found ''D. lineatum'' to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 90-130 years of age.<ref>Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.</ref> |

| − | ''D. lineatum'' was found to have increased occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished native longleaf pineland habitat that was disturbed by agriculture, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> | + | ''D. lineatum'' occurs primarily on sandy soils but can occur on a wide range of soils including sandy loam and sandy clay. It occurs in both full sun and partially shade,<ref name=fsu>Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Gary R. Knight, A. F. Clewell, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, J. P. Gillespie, Richard S. Mitchell, A.H. Curtiss, Wilson Baker, R. A. Norris, R. Komarek, T. MacClendon, - Boothes, Billie Bailey, William B. Fox, Sidney McDaniel, A. E. Radford, Clarke Hudson, and Michael B. Brooks. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Citrus, Duval, Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Madison, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker, Grady, and Thomas. Mississippi: Franklin, George, Madison, and Stone. North Carolina: Cumberland. South Carolina: Jasper and Marlboro.</ref> but having a prostrate habit it is not tolerant of very dense groundcover vegetation.<ref name="Robertson">Robertson, K.M. Observations on Pebble Hill Fire Plots in longleaf pine-wiregrass community on Pebble Hill Plantation near Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> It is occurs in both native communities and in areas with a history of soil disturbance<ref name=fsu/>. As well, it is a characteristic species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands habitat in Florida.<ref>Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.</ref> ''D. lineatum'' was found to have increased occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished native longleaf pineland habitat that was disturbed by agriculture, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> Additionaly, it was found to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.<ref name=Dixon>Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.</ref> |

Associated species include ''Desmodium ciliare, D. floridanum, D. ochroleucum, D. rotundifolium, D. laevigatum, Quercus laevis, Pinus elliotti.''<ref name=fsu/> | Associated species include ''Desmodium ciliare, D. floridanum, D. ochroleucum, D. rotundifolium, D. laevigatum, Quercus laevis, Pinus elliotti.''<ref name=fsu/> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| Line 51: | Line 49: | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | Populations of ''Desmodium lineatum'' have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> It is associated with frequently burned areas such as pinelands, pine flatwoods, savannas, and mature Longleaf pine-wiregrass uplands.<ref name=fsu/> However, it has also been found in fire excluded habitats, which show that ''D. lineatum'' is not fully fire dependent.<ref>Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.</ref> Hiers et al. (2000) found that flower production was significantly higher in burned areas compared to unburned areas. However, season of burn did not greatly influence flower production, duration of bloom, or timing of peak synchrony.<ref name=hiers>Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt, et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.</ref> It benefits most from high fire return intervals.<ref>Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.</ref> | + | Populations of ''Desmodium lineatum'' have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref><ref>Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.</ref> It is associated with frequently burned areas such as pinelands, pine flatwoods, savannas, and mature Longleaf pine-wiregrass uplands.<ref name=fsu/> However, it has also been found in fire excluded habitats, which show that ''D. lineatum'' is not fully fire dependent.<ref>Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.</ref> Hiers et al. (2000) found that flower production was significantly higher in burned areas compared to unburned areas. However, season of burn did not greatly influence flower production, duration of bloom, or timing of peak synchrony.<ref name=hiers>Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt, et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.</ref> It benefits most from high fire return intervals.<ref>Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.</ref> |

| − | <!--===Pollination and | + | <!--===Pollination===--> |

| + | <!--===Herbivory and toxicology===--><!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

===Diseases and parasites=== | ===Diseases and parasites=== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:47, 1 August 2024

| Desmodium lineatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. lineatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium lineatum DC. | |

| |

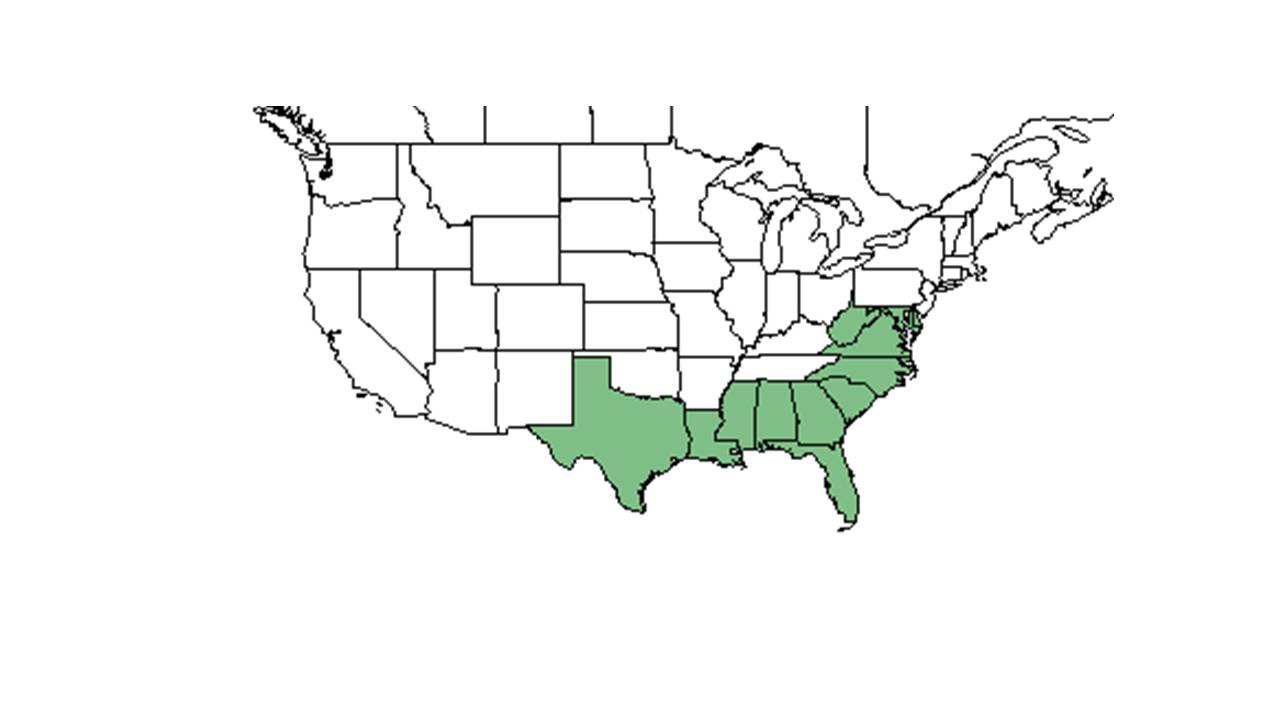

| Natural range of Desmodium lineatum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: sand tick-trefoil, matted tick-trefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: Meibomia arenicola Vail; Meibomia polymorpha (A. Gray) Small[1]

Description

Generally, for the Desmodium genus, they are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments." [2]

Specifically, for D. lineatum species, they are "perennial with uncinate-pubescent to glabrate, trailing stems, 5-7 dm long. Terminal leaflets ovate, rhombic, ovate or elliptic to orbicular, 0.7-3 cm long, 5-7 dm long. Terminal leaflets ovate, rhombic, obovate or elliptic to orbicular, 0.7-3 cm long, usually about ¾ as wide as long, finely reticulate, both surfaces glabrous or nearly so to densely uncinulate-puberulent and short-pubescent; stipules lance-attenuate to linear-subulate, striate, 2-5 mm long; stipels persistent. Inflorescence paniculate, usually densely uncinulate-puberulent and more sparsely uncinulate-pubescent; pedicels 0.6-1.6 cm long. Calyx densely puberulent and also sparsely short-pubescent; petals purplish, 4-6 mm long; stamens diadelphous. Loment usually of 2-3 segments, each 3.5-6 mm long, 2.5-3.5 mm broad, straight to somewhat curved along the upper suture while broadly rounded below, both sides and sutures very densely uncinulate; stipe longer than calyx tube, about equaling the longest calyx lobe, shorter than the stamina remnants." [2]

Distribution

Found in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. [3] It is primarily found in the panhandle and upper peninsular of Florida. [4] It is rarely found inland.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

D. lineatum is commonly found in sandhills as well as other dry woodlands and forests.[1] It is found in frequently burned upland longleaf and shortleaf pine native and old-field communities (Ultisols),[5][6] pine-oak sandhills (Entisols), pine flatwoods (Spodosols), and open areas within upland hardwood forests. Thrives in frequently burned (1-2 year fire interval) areas (Gilliam et al 2009).[6] D. lineatum is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7] A study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found D. lineatum to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 90-130 years of age.[8]

D. lineatum occurs primarily on sandy soils but can occur on a wide range of soils including sandy loam and sandy clay. It occurs in both full sun and partially shade,[6] but having a prostrate habit it is not tolerant of very dense groundcover vegetation.[9] It is occurs in both native communities and in areas with a history of soil disturbance[6]. As well, it is a characteristic species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands habitat in Florida.[10] D. lineatum was found to have increased occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished native longleaf pineland habitat that was disturbed by agriculture, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.[11][12] Additionaly, it was found to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[13]

Associated species include Desmodium ciliare, D. floridanum, D. ochroleucum, D. rotundifolium, D. laevigatum, Quercus laevis, Pinus elliotti.[6]

Phenology

D. lineatum commonly flowers between June and September and fruits between August and October.[14] However, it has been observed flowering and fruiting April through November (primarily in autumn).[6] Another source has observed D. lineatum to be flowering between April and June as well as between September and November with peak inflorescence in September and October.[15]

Seed dispersal

Seeds of this species are thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [16] The hooked hairs on the loments (legume pods) readily attach to fur as well as clothes.[9]

Fire ecology

Populations of Desmodium lineatum have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[17][18] It is associated with frequently burned areas such as pinelands, pine flatwoods, savannas, and mature Longleaf pine-wiregrass uplands.[6] However, it has also been found in fire excluded habitats, which show that D. lineatum is not fully fire dependent.[19] Hiers et al. (2000) found that flower production was significantly higher in burned areas compared to unburned areas. However, season of burn did not greatly influence flower production, duration of bloom, or timing of peak synchrony.[20] It benefits most from high fire return intervals.[21]

Diseases and parasites

The species can be infected by root-knot nematodes, including Meloidogyne arenaria, M. incognita, and M. javanica.[22]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Natural Heritage Program.[23]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-8. Print.

- ↑ NRCS Plants Database http://plants.usda.gov/java/

- ↑ ISB Plants Database http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/

- ↑ Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle (2003). "Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (Imperata cylindrica)." Plant Ecology 167: 237-245.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Gary R. Knight, A. F. Clewell, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, J. P. Gillespie, Richard S. Mitchell, A.H. Curtiss, Wilson Baker, R. A. Norris, R. Komarek, T. MacClendon, - Boothes, Billie Bailey, William B. Fox, Sidney McDaniel, A. E. Radford, Clarke Hudson, and Michael B. Brooks. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Citrus, Duval, Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Madison, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker, Grady, and Thomas. Mississippi: Franklin, George, Madison, and Stone. North Carolina: Cumberland. South Carolina: Jasper and Marlboro.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Robertson, K.M. Observations on Pebble Hill Fire Plots in longleaf pine-wiregrass community on Pebble Hill Plantation near Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 26 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt, et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- ↑ Quesenberry, K. H., et al. (2008). "Response of native southeastern U.S. legumes to root-knot nematodes." Crop Science 48: 2274-2278.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.