Difference between revisions of "Croton argyranthemus"

KatieMccoy (talk | contribs) (→References and notes) |

Adam.Vansant (talk | contribs) |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 14 users not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Common | + | Common names: Healing croton; silver croton; sandhill croton |

==Taxonomic notes== | ==Taxonomic notes== | ||

| + | Synonyms: none<ref name=weakley>Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Varieties: none<ref name=weakley/> | ||

| + | |||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

<!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The root system of ''Croton argyranthemus'' includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 103.9 mg/g (ranking 51 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 57.7% (ranking 14 out of 100 species studied).<ref name = "Diaz"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), ''Croton argyranthemus'' has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.22 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 103.9 mg g<sup>-1</sup>.<ref>Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.</ref> | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | It is extremely vulnerable to disturbance. One reason for this might be that it relies | + | It is extremely vulnerable to disturbance. One reason for this might be that it relies heavily on native species of ants for dispersal.<ref name="Kirkman et al 2004">Kirkman, L. K., K. L. Coffey, et al. (2004). "Ground cover recovery patterns and life-history traits: implications for restoration obstacles and opportunities in a species-rich savanna." Journal of Ecology 92(3): 409-421.</ref> It can be found in longleaf pine communities.<ref name=cumberland>Cumberland, M. S. and L. K. Kirkman (2013). "The effects of the red imported fire ant on seed fate in the longleaf pine ecosystem." Plant Ecology 214: 717-724.</ref> It can also be found in sandhill communities.<ref name="Stamp and Lucas 1990"/> It has been found on the edges of sandy oak-palmetto scrub, clobbered, cutover flatwoods, and pine-turkey oak flatwoods and sand ridges.<ref name="fsu">Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, D. Burch, Andre F. Clewell, M. Davis, Patricia Elliot, Robert K. Godfrey, C. Jackson, Walter Kittredge, Gary R. Knight, Robert Kral, Robert L. Lazor, Sidney McDaniel, John Morrill, John B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, Cecil R. Slaughter, John K. Small, S. S. Ward, E. West, Ira L. Wiggins, and Dorothy B. Wiggins. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Bay, Clay, Columbia, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Holmes, Jackson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Okaloosa, Polk, Santa Rosa, Taylor, Walton, and Washington.</ref> It has also been found to grow along disturbed areas like the wooded edges of powerline corridors. Growing in either moderate shade to full sun, this species grows in drying sandy loam in the uplands. ''C. argyranthemus'' has had variable changes in frequency and density in response to soil disturbance by roller chopping in northwest Florida sandhills. It has shown both regrowth and resistance to regrowth in reestablished native sandhill habitats that were disturbed by roller chopping.<ref>Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.</ref> The plant showed decreased occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has also shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished native savanna that was disturbed by agriculture.<ref>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref> ''C. argyranthemus'' was found to be a deacreaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.<ref name=Dixon>Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Associated species includes ''Crotonopsis, Paronychia, Tetragonotheca, Berlandiera, ''and'' Onosmodium.''<ref name="fsu"/> | ||

| − | + | ''Croton argyranthemus'' is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills community type and is an indicator species for the North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | |

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| − | It is a summer forb.<ref name="Kirkman et al 2004"/> This species has been observed to flower from | + | It is a summer forb.<ref name="Kirkman et al 2004"/> This species has been observed to flower from March to October with peak inflorescence in May and June; it has been obsereved to fruit from April to September.<ref name="fsu"/><ref>Nelson, G. [http://www.gilnelson.com/ PanFlora]: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016</ref> |

===Seed dispersal=== | ===Seed dispersal=== | ||

| − | Seeds have elaiosomes, and can be dispersed by ants such as fire ants | + | Ants are an agent of seed dispersal.<ref name=cumberland/> Seeds have elaiosomes, and can be dispersed by ants such as fire ants.<ref name=cumberland/> The seeds can also be dispersed explosively.<ref name="Kirkman et al 2004"/> Three of the ballistic euphorbs (''C. stimulosus, C. argyranthemus'' and ''S. sylvatica'') produce seeds with elaiosomes and all of the ballistic species are collected by ants, in particular ''Pogonomyrex badius'' Latreille (Long and Lakela 1971; N.E. Stamp and J. R. Lucas, personal observation).”<ref name="Stamp and Lucas 1990">Stamp, N. E. and J. R. Lucas (1990). "Spatial patterns and dispersal distances of explosively dispersing plants in Florida sandhill vegetation." Journal of Ecology 78: 589-600.</ref> |

| + | This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence. <ref> Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.</ref> | ||

<!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | <!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | ||

| Line 40: | Line 51: | ||

This species is fire tolerant and is included in the flowering plant survery – post burn – in Heuberger’s study.<ref>Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.</ref> | This species is fire tolerant and is included in the flowering plant survery – post burn – in Heuberger’s study.<ref>Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Pollination=== | |

| − | === | + | Pollinated mostly by small bees.<ref name=hawthorn/> |

| − | + | ||

| + | ===Herbivory and toxicology===<!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

| + | ''C. argyranthemus'' is an important game food plant: it is consumed by doves, quail, and deer.<ref name="Hebb 1971">Hebb, E. A. (1971). "Site preparation decreases game food plants in Florida sandhills." Journal of Wildlife Management 35: 155-162.</ref> It is the larval food plant for the goateed leafwing butterfly. It produces a milky sap to help defend from herbivory.<ref name=hawthorn>[[http://hawthornhillwildflowers.blogspot.com/2010/06/silver-croton-croton-argyranthemus.html]]Native Florida Wildflowers. Accessed: April 15, 2016</ref> | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

| − | == | + | |

| + | ==Cultural use== | ||

| + | Many species of ''Croton'' can be used in medicine, but oil derived from the plant can be highly toxic for canines and cause blistering on skin.<ref> Mueschner, W.C. 1957. Poisonous Plants of the United States. The Macmillan Company, New York.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

<gallery widths=180px> | <gallery widths=180px> | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==References and notes== | ==References and notes== | ||

Latest revision as of 16:54, 1 August 2024

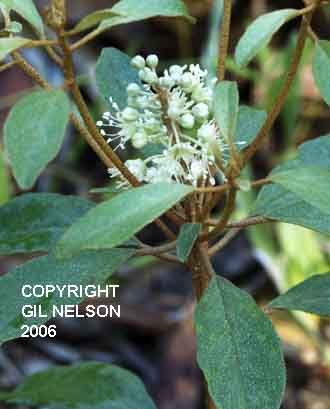

| Croton argyranthemus | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Euphorbiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Genus: | Croton |

| Species: | C. argyranthemus |

| Binomial name | |

| Croton argyranthemus Michx. | |

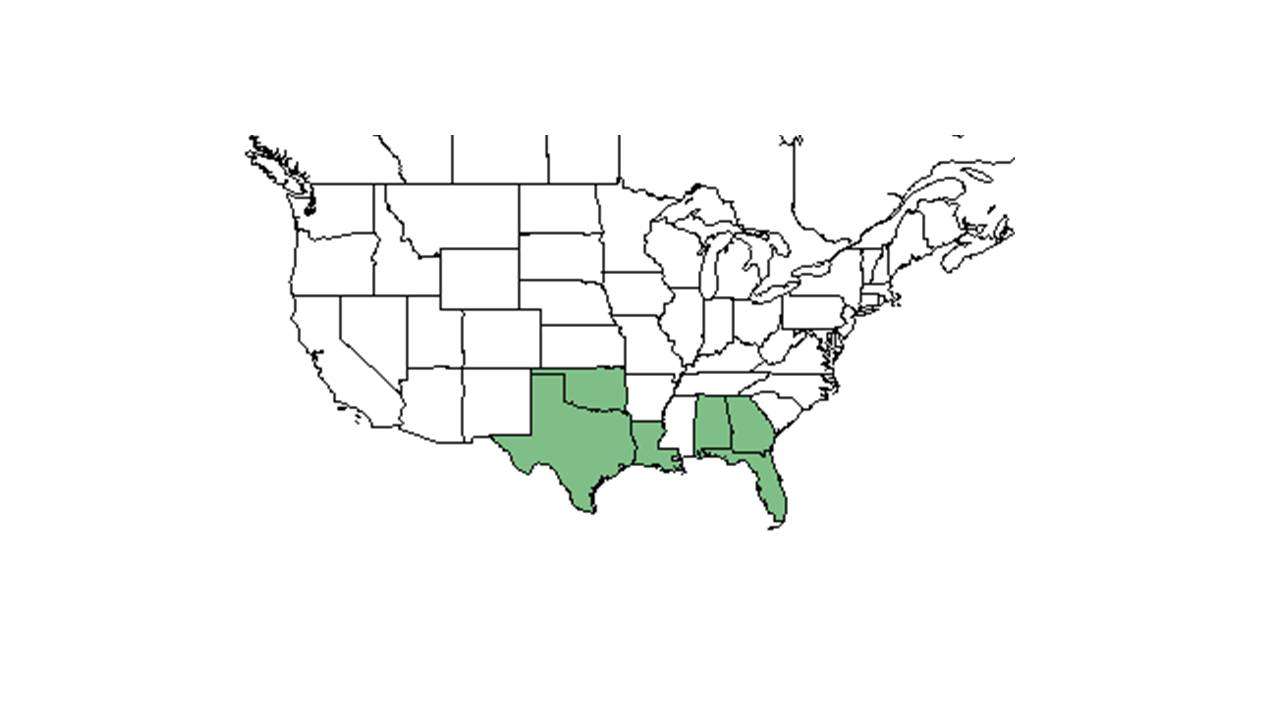

| |

| Natural range of Croton argyranthemus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Healing croton; silver croton; sandhill croton

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

The root system of Croton argyranthemus includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[2] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 103.9 mg/g (ranking 51 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 57.7% (ranking 14 out of 100 species studied).[2]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Croton argyranthemus has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.22 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 103.9 mg g-1.[3]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

It is extremely vulnerable to disturbance. One reason for this might be that it relies heavily on native species of ants for dispersal.[4] It can be found in longleaf pine communities.[5] It can also be found in sandhill communities.[6] It has been found on the edges of sandy oak-palmetto scrub, clobbered, cutover flatwoods, and pine-turkey oak flatwoods and sand ridges.[7] It has also been found to grow along disturbed areas like the wooded edges of powerline corridors. Growing in either moderate shade to full sun, this species grows in drying sandy loam in the uplands. C. argyranthemus has had variable changes in frequency and density in response to soil disturbance by roller chopping in northwest Florida sandhills. It has shown both regrowth and resistance to regrowth in reestablished native sandhill habitats that were disturbed by roller chopping.[8] The plant showed decreased occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has also shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished native savanna that was disturbed by agriculture.[9] C. argyranthemus was found to be a deacreaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[10]

Associated species includes Crotonopsis, Paronychia, Tetragonotheca, Berlandiera, and Onosmodium.[7]

Croton argyranthemus is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills community type and is an indicator species for the North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Phenology

It is a summer forb.[4] This species has been observed to flower from March to October with peak inflorescence in May and June; it has been obsereved to fruit from April to September.[7][12]

Seed dispersal

Ants are an agent of seed dispersal.[5] Seeds have elaiosomes, and can be dispersed by ants such as fire ants.[5] The seeds can also be dispersed explosively.[4] Three of the ballistic euphorbs (C. stimulosus, C. argyranthemus and S. sylvatica) produce seeds with elaiosomes and all of the ballistic species are collected by ants, in particular Pogonomyrex badius Latreille (Long and Lakela 1971; N.E. Stamp and J. R. Lucas, personal observation).”[6] This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence. [13]

Fire ecology

This species is fire tolerant and is included in the flowering plant survery – post burn – in Heuberger’s study.[14]

Pollination

Pollinated mostly by small bees.[15]

Herbivory and toxicology

C. argyranthemus is an important game food plant: it is consumed by doves, quail, and deer.[16] It is the larval food plant for the goateed leafwing butterfly. It produces a milky sap to help defend from herbivory.[15]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Many species of Croton can be used in medicine, but oil derived from the plant can be highly toxic for canines and cause blistering on skin.[17]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kirkman, L. K., K. L. Coffey, et al. (2004). "Ground cover recovery patterns and life-history traits: implications for restoration obstacles and opportunities in a species-rich savanna." Journal of Ecology 92(3): 409-421.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Cumberland, M. S. and L. K. Kirkman (2013). "The effects of the red imported fire ant on seed fate in the longleaf pine ecosystem." Plant Ecology 214: 717-724.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Stamp, N. E. and J. R. Lucas (1990). "Spatial patterns and dispersal distances of explosively dispersing plants in Florida sandhill vegetation." Journal of Ecology 78: 589-600.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, D. Burch, Andre F. Clewell, M. Davis, Patricia Elliot, Robert K. Godfrey, C. Jackson, Walter Kittredge, Gary R. Knight, Robert Kral, Robert L. Lazor, Sidney McDaniel, John Morrill, John B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, Cecil R. Slaughter, John K. Small, S. S. Ward, E. West, Ira L. Wiggins, and Dorothy B. Wiggins. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Bay, Clay, Columbia, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Holmes, Jackson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Okaloosa, Polk, Santa Rosa, Taylor, Walton, and Washington.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 [[1]]Native Florida Wildflowers. Accessed: April 15, 2016

- ↑ Hebb, E. A. (1971). "Site preparation decreases game food plants in Florida sandhills." Journal of Wildlife Management 35: 155-162.

- ↑ Mueschner, W.C. 1957. Poisonous Plants of the United States. The Macmillan Company, New York.