Difference between revisions of "Stillingia sylvatica"

(→Distribution) |

ParkerRoth (talk | contribs) (→Description) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

The root system of ''Stillingia sylvatica'' includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 413.9 mg/g (ranking 3 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 62.3% (ranking 50 out of 100 species studied).<ref name = "Diaz"/> | The root system of ''Stillingia sylvatica'' includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 413.9 mg/g (ranking 3 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 62.3% (ranking 50 out of 100 species studied).<ref name = "Diaz"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), ''Stillingia sylvatica'' has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 4.88 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 413.9 mg g<sup>-1</sup>.<ref>Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.</ref> | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| Line 35: | Line 37: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, ''S. sylvatica'' can be found in sandhills (FSU Herbarium),<ref name="sl"> Stamp, N. E. and J. R. Lucas. 1990. Spatial patterns and dispersal distances of explosively dispersing plants in Florida sandhill vegetation. Journal of Ecology 78:589-600.</ref> pine flatwoods, open pine-oak woodlands, recently burned pine-oak scrubs, longleaf pine-wiregrass stands, longleaf pine-turkey oak-wiregrass, and annually burned pinelands (FSU Herbarium). Substrate types include loamy sand, sand (FSU Herbarium), and siliceous, hypothermic ''Ultic haplaquod'' of the Pomona series.<ref name="Moore"> Moore, W. H., B. F. Swindel and W. S. Terry. 1982. Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest. Journal of Range Management 35:386-389.</ref> ''S. sylvatica'' does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.<ref>Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.</ref> | + | In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, ''S. sylvatica'' can be found in sandhills (FSU Herbarium),<ref name="sl"> Stamp, N. E. and J. R. Lucas. 1990. Spatial patterns and dispersal distances of explosively dispersing plants in Florida sandhill vegetation. Journal of Ecology 78:589-600.</ref> pine flatwoods, open pine-oak woodlands, recently burned pine-oak scrubs, longleaf pine-wiregrass stands, longleaf pine-turkey oak-wiregrass, and annually burned pinelands (FSU Herbarium). Substrate types include loamy sand, sand (FSU Herbarium), and siliceous, hypothermic ''Ultic haplaquod'' of the Pomona series.<ref name="Moore"> Moore, W. H., B. F. Swindel and W. S. Terry. 1982. Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest. Journal of Range Management 35:386-389.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ''S. sylvatica'' does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.<ref>Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.</ref> | ||

Associated species include ''Stillingia aquatica, Phlox floridana, Asimina longifolia var. spathulata, Lactuca graminifolia, Pterocaulon undulatum, Asclepias humistrata'' and ''Quercus hemisphaerica'' (FSU Herbarium). | Associated species include ''Stillingia aquatica, Phlox floridana, Asimina longifolia var. spathulata, Lactuca graminifolia, Pterocaulon undulatum, Asclepias humistrata'' and ''Quercus hemisphaerica'' (FSU Herbarium). | ||

| Line 45: | Line 49: | ||

===Seed dispersal=== | ===Seed dispersal=== | ||

| − | This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence.<ref> Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.</ref> It is dispersed explosively (up to 3 meters); seeds are forcefully expelled after the fruit matures and dries. | + | This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence.<ref> Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.</ref> It is dispersed explosively (up to 3 meters); seeds are forcefully expelled after the fruit matures and dries.<ref name="sl"/> |

| + | |||

| + | Though seeds may be dispersed in part by ants, studies show the seeds were attractive to fire ants but rarely moved by them.<ref>Cumberland, M.S. and Kirkman, L.K. 2013. The effects of the red imported fire ant on seed fate in the longleaf pine ecosystem. Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. Plant Ecol 214: 717-724.</ref> | ||

<!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | <!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | + | ''S. sylvatica'' seems to respond positively to burning. In an experiment by Greenberg (2003), and he noted that the percent cover of ''S. sylvatica'' was highest 16 months after a May burn.<ref name="g03"> Greenberg, C. H. 2003. Vegetation recovery and stand structure following a prescribed stand-replacement burn in sand pine scrub. Natural Areas Journal 23:141-151.</ref> Additionally, populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref><ref>Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Pollination=== | |

| − | + | ''S. sylvatica'' has been observed to host pollinators such as ''Perdita obscurata'' (family Andrenidae). The seeds of ''S. sylvatica'' contain elaiosomes and have been found in middens of Florida harvester ants, ''Pogonomyrmex badius''.<ref name="sl"/> | |

| − | The seeds of ''S. sylvatica'' contain elaiosomes and have been found in middens of Florida harvester ants, ''Pogonomyrmex badius''.<ref name="sl"/> | + | <!--===Herbivory and toxicology===<!--Common herbivores, granivory, insect hosting, poisonous chemicals, allelopathy, etc--> |

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:53, 3 July 2024

| Stillingia sylvatica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Michelle M. Smith | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta – Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Euphorbiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Genus: | Stillingia |

| Species: | S. sylvatica |

| Binomial name | |

| Stillingia sylvatica L. | |

| |

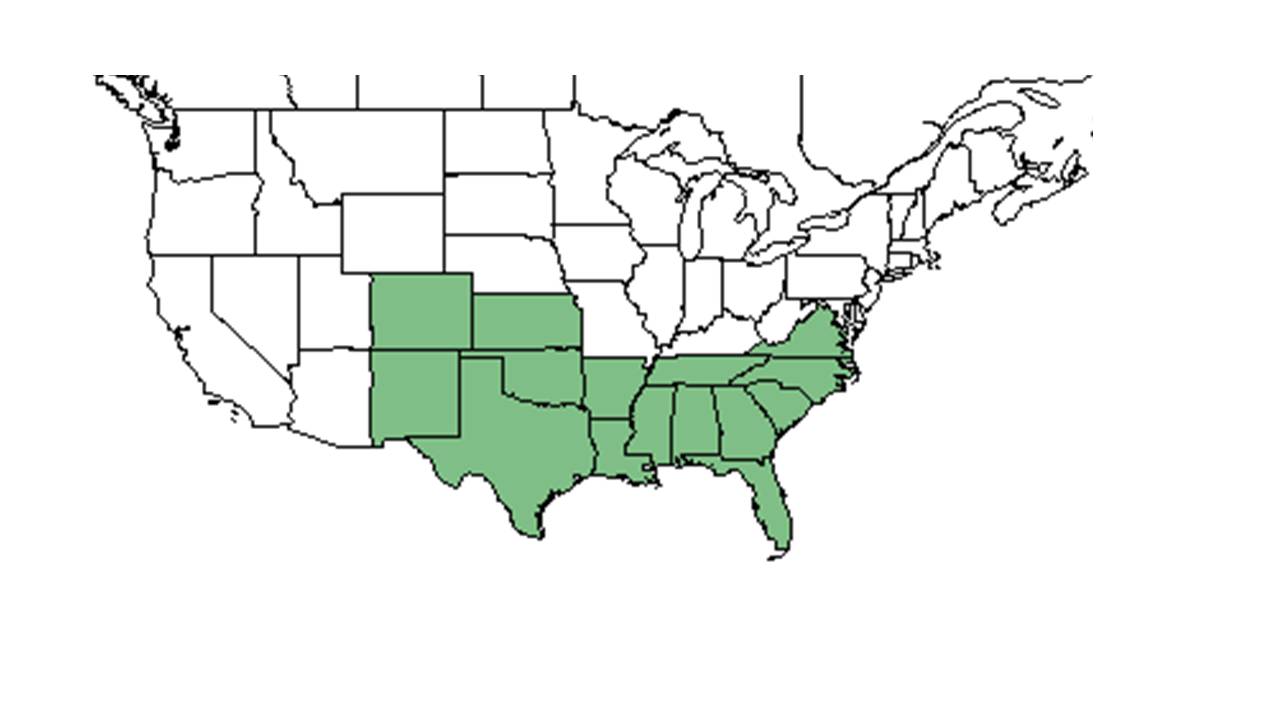

| Natural range of Stillingia sylvatica from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Queen's-delight

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: S. spathulata (Müller of Aargau) Small.[1]

Description

"Glabrous, monoecious, perennial herbs or shrubs with alternate leaves. Leaves finely crenate, the teeth with pointed, callous spicules, sessile or short-petiolate. Spike terminal, rachis with numerous large glands, the lower portion pistillate flowered, the upper staminate. Calyx 2-3 parted, yellow; petals none; stamens 2; stigmas 3, red. Capsules as long as broad, leaving a 3-lobed disc upon falling from plant. Seeds grayish white, ovoid; caruncle small."[2]

"Herbaceous perennial, to 8 dm tall, with few to numerous stems arising from a crown; stems branching only immediately below an inflorescence with 2-4 branches. These usually terminated in an inflorescence. Leaves elliptic, 3.5-9 cm long, 1-4.5 cm wide; petioles 0-4 mm long, base glandular-stipulate. Spike 5-12 cm long. Capsules 8-10 mm long. Seeds nearly smooth, 5-6 mm long."[2]

The root system of Stillingia sylvatica includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 413.9 mg/g (ranking 3 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 62.3% (ranking 50 out of 100 species studied).[3]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Stillingia sylvatica has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 4.88 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 413.9 mg g-1.[4]

Distribution

Stillingia sylvatica var. tenuis is endemic to subtropical Florida from Lake Okeechobee southward. The Miami Rocklands and Big Pine Key seem to be key speciation areas.[5]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, S. sylvatica can be found in sandhills (FSU Herbarium),[6] pine flatwoods, open pine-oak woodlands, recently burned pine-oak scrubs, longleaf pine-wiregrass stands, longleaf pine-turkey oak-wiregrass, and annually burned pinelands (FSU Herbarium). Substrate types include loamy sand, sand (FSU Herbarium), and siliceous, hypothermic Ultic haplaquod of the Pomona series.[7]

S. sylvatica does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[8]

Associated species include Stillingia aquatica, Phlox floridana, Asimina longifolia var. spathulata, Lactuca graminifolia, Pterocaulon undulatum, Asclepias humistrata and Quercus hemisphaerica (FSU Herbarium).

Stillingia sylvatica is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills and North Florida Subxeric Sandhiils community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[9]

Phenology

S. sylvatica has been observed flowering April through August with peak inflorescence in April and May (FSU Herbarium).[10]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence.[11] It is dispersed explosively (up to 3 meters); seeds are forcefully expelled after the fruit matures and dries.[6]

Though seeds may be dispersed in part by ants, studies show the seeds were attractive to fire ants but rarely moved by them.[12]

Fire ecology

S. sylvatica seems to respond positively to burning. In an experiment by Greenberg (2003), and he noted that the percent cover of S. sylvatica was highest 16 months after a May burn.[13] Additionally, populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[14][15]

Pollination

S. sylvatica has been observed to host pollinators such as Perdita obscurata (family Andrenidae). The seeds of S. sylvatica contain elaiosomes and have been found in middens of Florida harvester ants, Pogonomyrmex badius.[6]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Historically, the plant's roots were mashed and boiled and given to native women after giving birth, and it was used to treat menstrual irregularity. In the south, it was used to treat constipation and induce vomiting. It was also used as a treatment for syphilis, skin diseases, pulmonary issues, and liver problems.[16] This species should be used with caution, as cyanide has been detected within the plant.[17]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 667. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Stamp, N. E. and J. R. Lucas. 1990. Spatial patterns and dispersal distances of explosively dispersing plants in Florida sandhill vegetation. Journal of Ecology 78:589-600.

- ↑ Moore, W. H., B. F. Swindel and W. S. Terry. 1982. Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest. Journal of Range Management 35:386-389.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 14 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Cumberland, M.S. and Kirkman, L.K. 2013. The effects of the red imported fire ant on seed fate in the longleaf pine ecosystem. Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. Plant Ecol 214: 717-724.

- ↑ Greenberg, C. H. 2003. Vegetation recovery and stand structure following a prescribed stand-replacement burn in sand pine scrub. Natural Areas Journal 23:141-151.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Burrows, G.E., Tyrl, R.J. 2001. Toxic Plants of North America. Iowa State Press.